Dan Lago, David Krauss, and Fred and Linda Fisher. 8-7-2023

Introduction

The Barlow knife has a long history, but the larger version whether called “Grand Daddy” or “Daddy,” has not had as much attention compared to its very practical small-sized pocket knife. The original Barlow has a long history from around 1670, from the work of Obadiah Barlow in Sheffield, England, although many others’ claims have been made (History of Barlow Knives (barlow-knives.com).These knives measure about 3.5” closed compared to the bigger, more modern, knife at 5” closed.

Figure 1. A comparison of two Queen-made Barlows, “standard size” #22 (left), and Daddy Barlow, from 1976 (right). This article focuses on the bigger knife.

Modern American cutlery companies such as Case, Russell, Schrade, Camillus, Robeson, and Utica made large Barlows from the 1920s -194os. Perhaps the most famous is Case’s Grand Daddy Barlow #43. American’s have favored the large Barlow for outdoor farming and hunting uses and they were usually plain single clip blade knives with wood or sawcut bone handles. As shown in the photos, these knives are “barehead” style, meaning that they have no cap end bolster. To our knowledge, no traditional Barlow, Daddy, or Granddaddy Barlow, have been produced by those other American cutlery company with a bolster on both ends of the knife. We will return to this fact at the end of this article.

Queen seemed to discover the Daddy later than many other modern cutlery companies but they have made many recently and represent a very interesting aspect of the company’s shift into collector-oriented knives. This piece will summarize Queen’s history with the large Barlow knife from its early history with Schatt & Morgan through Queens emphasis on “tool-oriented” knives in the mid-20th century. We will discuss the development of the large Daddy Barlow that characterized Queen under Servotronics in the late 20th century until purchase by the Daniels Family in 2012, and finally, until the company went out of business in 2017. In this review, we mention 33 different large Barlow knives queen has produced, with 31 shown in photos.

History

A search of Schatt & Morgan catalogs (reproductions by David Clark, 2010) do not show any “Granddaddy Barlows: or “Daddy Barlows”. In the listing of pattern names (prepared by David Clark, see: SM-Pattern-Numbers-Pat-number-sort-1.0-1.pdf (queencutleryguide.com) or images of the many knives offered in the catalogs for both 1903 and 1907. Especially in the 1907 catalog there are some knives that look somewhat like a large Barlow, with a straight handle and a large clip blade (see for example, in 1907, pages 58, 82, and 83), but they are usually listed as “heavy jacks.” No exact sizes are provided in the catalogs but many of the larger knives in this catalog (like swing guards, and English jacks are about 4.5” while the daddy Barlows are usually 5” closed – so, not a definitive match. There is only one Barlow knife (standard size), #100 on page 31 in the 1903 catalogs and none shown in the 1907 issue. So, there is no history of Schatt & Morgan making big Barlow knives such that they were profiled in the only available catalogs.

Queen City never produced a catalog and most of their pocket knives are around 4” or less closed. Large Daddy Barlows do not characterize their knives that have come down to us in most collections. Many of their fixed blade knives were shorter than an open large Barlow and would have been preferred for heavy work.

Queen Cutlery after WWII made a different decision for a large folding knife and developed the “Big Chief” (#45) as a modern approach for a tool giving good value for practical use by taking advantage of aluminum casting technologies gained during the war and development of improved stainless steels. We think that knife filled the role of a Daddy Barlow for Queen for many years, with the same traditional size at 5” closed and 9” open. The knife had the classic large Daddy Barlow shape – straight handle gradually widening at the base of the hand. The “Big Chief” knife was produced from 1953-2009 (in catalog listings but was available to buyers until about 2014, at the factory store). While considerable skill was required in casting the large aluminum handle, the knife had only four parts, (blade, handle, backspring, and pin) and could be assembled in under a minute with the required jig. Several different blades but the same aluminum handle was produced over its 56-year run. See Figures 2, 3 and 4 for photos of the Big Chief.

Priced very low (first offered in 1953 at 99 cents), easy to complete, and extremely durable, the knife was one of Queen’s most successful offerings – it led sales for years. In the 21st century, tempering problems on the backsprings caused the demise of this knife. This knife helped open-up southern markets because with stainless blade and aluminum handle the knife was very suited to ocean climates and fishing tackle boxes. But it did NOT provide an incentive for early exploration of other large Barlow-type knives – why develop an internal competitor for their best seller?

Figure 2. A Queen “Big Chief” #45, with traditional clip blade, with a variety of tang stamps from its offering in 1953 through 2014 are shown. (Fred and Linda Fisher photo).

Figure 3. Two later versions of the Big Chief. The top knife (#45F) is shown with a narrow “Fillet” blade. The lower knife has the usual clip blade but is shown with a massive liner lock and was made for only a few years in the later 1970s, with the patent number used by Queen in all its aluminum handled knives. (Fred and Linda Fisher photo).

Figure 4. Two more versions of the Big Chief. The top knife has a serrated blade, a bale at the lower end, and an “easy open” cut-out on the handle. This knife was an SFO for a company “Divers Supply.” The lower knife was a Divers Knife (#45D). (Fred and Linda Fisher photo)

Queen transferred model numbers. The model number for the Daddy Barlow when Queen did start to produce them was #71) which belonged earlier to the coho or salmon fillet knife available from 1972-1977. It was a very large fishing knife with a spoon at the end of the handle for gutting or removing roe. Then the model number was used very briefly for the “John Henry Express switchblade” at the end of Queen’s business life. In other words, there was not a long history of making named daddy Barlow knives for Queen other than “the Big Chief”.

Collector Knives Emerge

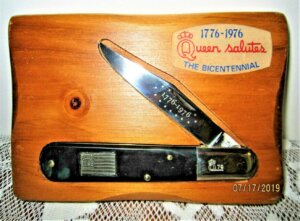

Queen did produce a traditional large Barlow in 1976, with smooth Black Delrin handles and a clip blade mounted on a pine board for the national Bicentennial celebration. The knife had blade etching, large colonial flag shield, and a stamped bolster that highlighted the year of production; all serious attempts to make a collector knife, seen in Figure 5. The knife was the first time Queen serialized a knife (on the pile side bolster). It was to be made in an edition of 15,000, but never approached that target. Many were sold, but blades and frames were left in inventory.

Figure 5. Queen’s 1976 “Bicentennial Barlow” (sold as model #1450). Though this knife has the shape and blade of a traditional large Barlow, it was not marketed as such. In part, this might have been to connect it to the company’s first collector knife – the Drake Well Commemorative Barlow in 1972. (Internet Photo).

Figure 6, shows two additional early large Barlows that were spun off the 1976 Bicentennial Barlow using remaining parts. Queen faced severe competition in the late 1970s and need to modernize its product line. The “Rawhide” series was one response, using stabilized wood handles and stainless 440C blades. The large Barlow knife on the bottom in Figure 6, is one of their ways of adding value to the Rawhide series. This knife was only produced in 1980 and 1981 according to price lists, and was not included in the 1980 catalog roll-out for the Rawhide Series. It was not labeled as a “Grand Daddy” or “Daddy” – just as the “Rawhide Barlow.” Because of its rarity it is one of the Rawhide series knives that is very hard to find.

The middle knife in Figure 6, with the tang stamp of Smoky Mountain Knife Works was also produced in the 1980s from parts left over from the 1976 Bicentennial Barlow. It uses a Delrin handle material used only by Queen that was also used in 1976 on an early version of the Mountain Man #1446 (and a few other knives over the years). Queen never labeled this material and collectors have called it either “tiger stripe” or “buffalo horn.” In almost every case, this handle material showed severe shrinkage and it is no surprise that Queen unloaded it on a contracted relatively low-cost knife.

Figure 6. The top knife is the Bicentennial Barlow with two knives made with left over blades and frames in the early 1980s. One can see the slight difference in nail nicks on the two later produced pieces, but otherwise they are identical.

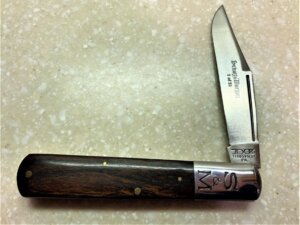

In the later 1980s, and on through the 1990s, Queen began to complete contracts for others that provided them with a skilled set of cutlers and experience in producing higher-quality knives in limited editions. That can easily be seen in a series of Daddy Barlows they produced beginning in 1995 through 2003, under the Robeson ShurEdge trademark. The first Robeson “Daddy Barlow” was produced by Queen in 1995 (Robeson number, #612224) with a large single clip blade and represents the model for the other two – it is the first time that Queen used a signature long bolster for a large knife and clearly harkens back to an earlier time in pocket knives.

Figure 7. A Series of “Daddy Barlows” under the Robeson ShurEdge brand made by Queen (see the 1995 catalog for the “Daddy” name). The jigged bone in the front was cataloged in 1995. The sawcut bone in the middle was cataloged in 1999-2000, and the smooth bone in 2003. All three are versions of the famous “strawberry bone” that was associated with the Robeson name.

The first two Robesons are cataloged and the edition size is not known, but would have been limited, probably less than 400 for each. The smooth bone in 2003 has a matchstriker long pull and a very unusual bowtie shield not seen in any other Queen-produced Robeson knife. It was released in an edition of 100 knives and is a very hard knife to find. The comparison of the Queen large Barlows in earlier 1970 and 1980 years with these three is striking – Suddenly beautiful knives!

Figure 8. Queen produced this Dan Burke special factory order after 2002, since the pile side tang stamp shows a Queen stamp with use of D2 steel. The light orange sawcut bone gives the knife a very traditional feel. There is no indication of how large the edition was. The Dan Burke marked blade was later used on other Daddy Barlows, (with white or black acrylic covers) but we are not sure of their origin. They might be SFO’s or knives simply made from spare parts either at the factory or privately.

Figure 9. This Daddy Barlow was an SFO in the “Premier” series of Schatt & Morgan knives produced in 2006, for Clarence Risner, Queen’s main distributor of their knives for many years. Risner was a stickler for detail and added several key details that Queen used subsequently for many of its large Barlows, as we shall show.

Like the Robeson’s before it, The Queen-produced Robeson knives are named “Daddy Barlow” (not “Grand Daddy”) and used a large “signature” bolster with the bold S & M initials in black. This type of bolster was not seen in early Schatt & Morgan knives nor in the early reproductions begun in 1991. The signature bolster first appeared in the 2003 small Barlow in the XIII series. Risner and Queen cutlers decided to add it to the large knife and added the secondary pen blade. This “Premier” knife also shows the model number #71 for the first time as the final two digits of its Schatt & Morgan model number on the blade. It also added the matchstriker pull and used the finest jigged bone they could find. Like early large Barlows, this knife used a barehead handle consistent with the traditional pattern design Queen used in later knives. This knife was limited to a run of 350 knives.

Figure 10. The 2007 Daddy Barlow from the XVII Schatt & Morgan Keystone series in “keystone state red timeworn jigged bone,” also in barehead style. Edition size was 600 for this pattern.

Parenthetically, it can be mentioned with the relatively very large and sharp secondary blade and the large handle, this knife can make a very powerful cutter. While most of these knives have resided in display boxes, these knives, are still very effective cutting implements. Sometimes one can find these knives showing evidence of a hard life and sharpening in everyday use on the secondary market. One of the reasons was that this pattern was well known for very strong backsprings. It had to be initially strong to operate with such a large blade and therefore could last longer under heavy use. Frankly, these were (are) great user knives in our opinion, although we would generally use a belt sheath because these knives are indeed heavy in the pocket.

Figure 11. The 85th anniversary Daddy Barlow in a single blade, barehead format with a stanhope lens, also produced in 2007. The Stanhope lens at the bottom of the handle allowed a glimpse into the founders of the company and was very expensive to build into the knife; one of only two knives the company ever made with this feature. For more information on Queen Stanhope knives, please refer to: stanhope-lens.pdf (queencutleryguide.com) by Fred Fisher and myself.

Some people do not recognize the Stanhope feature, probably mistaking it for a lanyard hole. The knife uses the old “Queen City” tang stamp and shows the serial number for each knife on the blade. Only 300 of this knife were produced.

Figure 12. The 2008-09 File & Wire Daddy Barlow with spear blade and small clip secondary blade – both unusual choices and the primary blade made with ATS 34 stainless steel. This knife was advertised with darker green “Pennsylvania mountain moss green bone” worm grooved handles, but is usually found in the lighter bone color of the example shown in this photo.

Figure 13. A large Fisherman’s Barlow Produced in about 2012 under the “Queen City” script tang stamp and jigged brown bone covers in a rough pattern to help keep a good grip. The knife has a seldom-used bowtie shield, and one can see a hint of brass liners. Again, a barehead, single blade format. (Internet photo). This knife was produced in an edition of 300.

This knife seems odd to us because Queen was well known for using stainless steels and this blade is carbon steel with a satin finish which is generally not used for fishing knives. Carbon steel requires careful cleaning and maintenance after every use. This knife was probably aimed at modern collectors, it recalls earlier Remington large Barlows which might have been used as the pattern.

Figure 14 shows a much more refined, polished version of the Large Barlow Fisherman knife produced two years later under the very limited brand of “Tuna Valley”, also made by Queen in the Titusville Cutlery. The Tuna Valley version now has a mirror polished blade, and though the steel is not mentioned, the general shape of the blade, the nail nick, and the same 12 points of the fish scaler section, are essentially identical to the Queen City version from two years earlier.

Figure 14. A Tuna Valley “Fish Scaler” large Barlow made by Queen Cutlery in 2014 in beautiful Torched Sambar Stag, in an edition of 50 knives, with another 50 in Amber stag, and 50 more in smooth Buffalo Horn. Because of the width of the stag, and the way it expands at the base of the handle, this knife has a wonderful feel in your hand. Although a rare knife, this feels very much like a working knife. Refer to Carl Bradshaw’s summary of Brief-TV-History.pdf (queencutleryguide.com) for Tuna Valley knives through 2017 to see documentation for the edition size in the three different handle materials.

Figure 15 shows a very unusual amalgam of the two previous Fishing Barlows. It is an example of one of the small mysteries that from time to time may present themselves to dedicated Queen knife collectors.

Figure 15. Stag handles on this Queen City Fisherman’s large Barlow is a an “easy open” style (showing pile side). It has the Queen City script tang stamp with a satin finish on the blade and DFC “carbon” tang stamp on the pile side. While, the blade is identical to the factory original version, the stag handles are also identical to the knife in Figure 14, with the same easy open cut-out, and the same stainless (or nickel silver?) liners as the Tuna Valley Fish Scaler. However, unlike either of the two knives it matches, the knife is hafted with pins that were not “spun,” but hammered and filed as can readily be seen on the main backspring pin and nearby flattened sections of the stag covers. To our knowledge all Queen factory pins have been spun since the early 1950s, not hammered and filed as this knife shows. Still, a very attractive knife.

Figure 16. A Daddy Barlow made in 2014, with the same blade choices (spear and secondary clip blade) as the 2008 knife (Figure 12) but not showing ATS34 steel. The knife shows “Queen Cutlery Show 2014” on the secondary blade and an edition of 100 knives. Sometimes this knife can be found without the show etch.

Beginning in 2016 and through the end of 2017, when they stopped producing knives, Queen, in the Daniels Family era, began making many very small editions of Daddy Barlows using the design elements originally featured in the 2006 Clarence Risner “Premier” Barlow (Figure 9). They are shown in Figures 17 through Figure 23. Some of these knives do not show a name (“Daddy” or otherwise), or have etches that show a model number. There is a possibility some were sold without box labels. Still, in our opinion they are all clearly within the Daddy Barlow family because they use the basic frame of the #71 pattern.

Figure 17. A large two-blade File & Wire Barlow with a spear blade and pen secondary blade hafted in black curly maple with a matte finish in the traditional barehead format. The signature bolster is strong and the shield matches the blade etch. Unlike this knife, all F&W knives historically were hafted in top quality jigged and dyed bone and sported highest quality stainless blades. This knife has carbon steel blades with high polish and strong etch. No edition size is shown.

Carbon steel was less expensive for Queen to obtain in its last years. Although most collectors generally prefer stainless steel blades, such a knife with carbon steel would be easier to sharpen, and would take a very fine edge, so this knife could provide good service in hard use. In the last few years, we see different secondary blades and finally moving to single blade designs, as the company was coping with financial concerns.

Figure 18. A single blade Schatt & Morgan Large Barlow in black micarta with a very Mother of pearl keystone shield. These knives in slightly different handle materials and blades are frequently seen in secondary sales sites, and though the edition size is 25, small changes in these knives might account for how frequently they are seen. One would expect much more emphasis on the final polish on both blade and handle to “earn” its pearl shield on the knife pictured above.

The pearl shield was first used in 2002 in the XII series (100th year anniversary) with smooth buffalo horn handles and gold blade etches and is considered my many collectors to be the best single year of the Keystone series.

This knife came with a box and a label calling the knife “Grand Daddy Barlow” and an odd model number, #75, customarily used by Queen for a large fixed blade knife (see Figure 19.) It is unclear to the authors why the name was changed from “Daddy” to “Granddaddy” for this final series, or why the number was changed, since all the large Barlows were made on the 5” frame. These comments are not meant to discourage collectors from these knives, since the issues might be associated with only certain individual knives, and very high-quality knives might still be found. It is to highlight that financial pressures place severe challenges on making the best knives and collectors should therefore be more careful in studying a knife before they purchase.

Figure 19. Box for the Black micarta knife in Figure 18.

Figure 20. A large Queen-made Barlow in “lightning wood” in a single blade, barehead format. The lack of a shield is a cost savings as is the use of wood for handles. The lightning wood handle does highlight the dramatic and unusual electricity burns created in the process and may provide some additional grip and therefore, diminishes the need for a shield. Some other Internet photos show an edition of 25 for this version. (Internet photo).

Figure 21. A Large Schatt & Morgan single blade Barlow with smooth, brown Maple burl handles in the traditional barehead format with a keystone shield. This knife blade is etched “Factory Sample.” Perhaps, because the wood handle was very limited in supply – clearly not a sample of the pattern in the usual sense, because a number of previous Daddy Barlows had used wood covers and a similar blade. This knife is one of very few knives that does not show the blackened bolster letters. perhaps a sign of financial difficulties in the last period of business as one more operation in completing a knife is omitted. (Internet photo)

Figure 22. A Schatt & Morgan Barlow with a single carbon steel blade, this time hafted with figured Walnut. The pile side of the blade is labeled “NCCA show, 2018.” This might be one of the very last large Daddy Barlows Queen made given the date of this etch. Knife produced in edition of 25.

Cap End Versions labeled and sold by Queen as Daddy Barlows

There are many different terms for the various parts of a traditionally constructed pocket knife, associated with the various cutleries who produce them. We regard Great Eastern Cutlery as one of the very best in this process (if not the VERY best) and they have a public site which clearly describes their nomenclature. We adopt their terms for this discussion.

“The end of the pocket knife opposite the primary blade end is called the cap end. If there is a bolster, it is the cap end bolster or just plain cap end.” (Knife Terminology | Great Eastern Cutlery).

Returning to a topic we mentioned in our Introduction, in Queen’s last three years they produced numerous knives on the large Barlow frame but with a unique finish in their construction: instead of the usual, and completely traditional, “barehead” at the cap end of the knife, some of Queens have a large cap end bolster.

Since traditional large Barlows are all barehead, some think these new versions are not truly Daddy or Granddaddy Barlows. We, of course, will allow collectors and cutlery companies to adopt whatever name they choose. We do think they are of the “Barlow Family,” because of the identical frame used in constructing them. It is useful to the reader to compare the two Queen large Barlows in Figure 23 to view the basic similarity. Samples of others by Queen are shown in figure 24 through 29.

Figure 23. Two Queen made large Barlow knives, with the traditional Daddy Barlow on bottom (2007, Schatt & Morgan Keystone) and the 2015, “Deluxe Quart Barlow” with a File & Wire shield above it. Despite differences in handle materials and blades, one can see the two patterns are very similar in form, both width and length, with the notable and significant change for a “Barlow”, a cap end bolster on the upper knife.

Figure 24. a “Deluxe Quart Barlow” by itself, File & Wire shield, in torched Sambar stag with two full-size blades. With master blade (clip) in ATS 34 made in 2015 (p. 2 catalog.) This knife is still listed as #032171 as a “large Barlow” and produced in an edition of 400.

The reader may recall that all large Queen-made Barlows were bareheaded until 2015, when the stag File & Wire Quart Barlow was introduced by Daniels Family Cutlery era (Figure 24) during the last three years of their operation. Figures 14 and 24 are example that Ken Daniels, owner of Queen at this time had a life-long affection for well-done stag handles, in both large patterns and much the smaller “Gentleman’s stag” series. It must be admitted in the final years of the company’s existence that quality control did suffer. But it is also completely true, from our perspective, that some beautiful knives were made during this time, including some of these Daddy Barlow cap end bolster knives.

Why would a cutlery company noted for the manufacturer of traditional pocket knives change the appearance of their Barlows? One might argue that a cap end bolster strengthens a heavy-use knife; protecting the handle material. It is an addition that could serve a large knife well, though it does add a bit more weight to the knife. But most of Queen’s Barlows were made for collectors and there were other large folding knives available at lower prices that were suitable for such tasks. If one assumes that various lengths of expensive handle materials were available, as seen on the knife above, the extra ½” of handle material would increase in the cost of a knife much more than adding a chunk of nickel silver, and the end cap bolster could compensate for the shorter handle material.

In hindsight we now know that Daniels Family Cutlery faced increasing financial pressures that eventually drove Queen to declare bankruptcy within three years of making their first cap end bolster “Barlow.” It is likely that during that time they were forced to use as much existing materials in inventory, and to acquire less expensive materials such as carbon steel and wood handle coverings, and to omit some steps that were required at times to complete a knife of Queen’ s traditional high standards, such as mirror polishing of blades. Still, the use of the cap end bolster was a creative solution and they sold well in the last years. Some might have been converted to hard-use knives with their large carbon steel blades, strong springs, and big handles, so collectors will also need to look for signs of use if seeking these examples. Time will tell which knives hold their value in coming years.

Figure 25. A large Queen “Barlow” with smooth mammoth ivory and traditional clip and pen blades, but with a cap end bolster, which adds protection to the mammoth scales. The knife shows a blade etch of 1 of 10 produced and it probably dates from 2016-2017. (Internet photo).

Figure 26. A two-blade Schatt & Morgan with clip blade, match striker pull, and cap end bolster in black micarta. No black in the initials on the top bolster, no etch, or edition size. The steel is unnamed. Some very similar knives were made in smooth buffalo horn with edition sizes noted. The company made an unknown number of knives in this pattern with the cap end bolsters in their last year of business. (Internet photo).

Figure 27. Schatt & Morgan single blade with rarely seen ATS stainless steel in a large Barlow pattern in oiled natural bone, though with a Keystone shield, but the usual file & Wire shield for ATS34, with a cap end bolster in an edition of 30 knives.

Figure 28. A large File & Wire Barlow with a single spear blade with white bone handles and with the cap end bolster. Note the blade is unlike the 2008 version in that the nail nick is higher and the large swedge is missing, so it is more like Figure 17. The edition size is unknown. (Internet photo)

Figure 29. A two-blade Schatt & Morgan Barlow in Carbon Steel, in a cataloged handle material, “Queen blue bone,” no shield, with traditional clip blade with match striker pull, secondary pen blade, and a cap end bolster. The blade is etched “1 of 30”.

Although we profile seven knives above, their editions were probably very small, and there was never a catalog or a public record that these knives were being offered for sale. They are shown here because we try to be thorough and to include representations of all known versions of Queen made Daddy Barlows, and large cap end bolster knives. It is entirely possible that additional knives of this type may someday emerge from collections. We encourage readers to assist us in this effort and to send us a photograph so we may add their unusual Queen “Barlow frame” knife to this collection for the benefit of all collectors. Special factory orders for this Barlow pattern are not well documented.

In closing, we show a Northwoods Daddy Barlow Figure 30 a Queen-made reproduction of a Scagel Daddy Barlow in stag, that is well documented, and a special treat to see for all who favor the traditional large Barlow knife.

Figure 30. Queen made this knife as a modern reproduction of a classic Scagel barehead Daddy Barlow as an SFO for David Shirley and Northwoods Cutlery in the early 21st century. It is a very low numbered edition of a beautiful knife. It is 5” closed and built to the same measurements as the Queen-made Daddy Barlows. It seems reasonable to close our discussion by paying homage to Queen’s production of this very “old school” Daddy Barlow.

Conclusion and Summary

So, reviewing large Barlows shown in this article, its clear that Queen liked this pattern and produced it beginning in 1995 with the Robeson offerings, in many Keystone versions in the 2000s. The company generally used superior handle materials, different blade configurations, steels, and a variety of shields consistent with their premium lines. These knives were clearly aimed at pocket knife collectors. In their final years Queen often produced knives in very low editions, and some of the knives they produced were of varying quality. Collectors may vary in their opinions of Barlows with cap end bolsters, depending on the priority they give to traditionally designed and executed knives.

One would need to be patient in collecting these big pocket knives because of the small editions produced. As we stated earlier, it is always useful to thoroughly examine any knife before purchase, to make certain the quality of a specific knife is satisfactory to you and fits your collecting priorities.

NOTE: This is a first edition and we hope it will encourage collectors who have versions of Barlow knives not shown in this paper, or who have corrections or additions to suggest to contact us. Thank you.

Any photographs taken from the Internet are assembled only to provide samples of this pattern’s variability. They are each labeled “Internet Photo” and we thank the those who posted them on public sites. All others are from the authors’ personal collections.

References

Brief-TV-History.pdf (queencutleryguide.com). For Tuna Valley resources

Clark, David (2010). Reproduction of Schatt & Morgan 1903 and 1907 Catalogs. (1903, 52 pp, 1907, 128 pp). Published by Lois and Clark Publications, 349 Windsor Dr., Marietta GA 30064. Available from: http://www.knifeworld.com/schatt-morgan-catalogs1.html or https://www.allaboutpocketknives.com/catalog/9580-early-schatt-and-morgan-catalog-reproductions

Clarence-Risner-1-2020.pdf (secureserver.net)

History of Barlow Knives (barlow-knives.com)

Model-45-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Model-71-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

SM-Pattern-Numbers-Pat-number-sort-1.0-1.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)