Dan Lago,

We gratefully Acknowledge contributions by Fred and Linda Fisher and to David Clark for expertise shared and images used.

Introduction

To define the swing guard pocket knife, I mean a folding knife that uses a back lock to hold the blade when open, and has small metal bars (the “swing guard”) attached to the tang on either side of the blade with one thru-pin. As the blade opens, the guards swing down to lock against the handle and provide some protection for the user’s hand.

Queen and its predecessor Schatt & Morgan had a long and complex history with this knife pattern and they made it is more versions than any pocketknife they ever produced. We plan to produce several articles to give collectors a solid summary of this very nice and popular knife. Our plans include:

- Introduction and history of Schatt & Morgan and Queen City swing guard Knives from 1902-1945; (find on “Blogs)

- Queen Catalog and Special Projects versions of the swing guard from 1945-2017, including Robeson ; (find on Blogs)

- Queen Special Factory Orders (SFO) for clients who favored this very popular knife from 1991-2017; (find on Blogs)

- An Excel database with provides an overview of Queen Cutlery swing guards from 1991-2017, (find on Queencutleryguide.com under “knife articles”)containing 123 knives.

Historical perspective.

Several internet sources claim folding knives were heavily in use by the Romans by 500 BC and some surviving models were swing guards and highly decorated. One account gives Spaniards credit for popularizing a folding lock back knife in the 1400s. Neil Punchard (2017) states, “hand guards have been used on knives and swords since about the beginning of cutlery for an essential purpose, to protect the hand.” He reports that the first swing guard knives are not known, but they clearly existed by the early to middle 1800s throughout Europe. Clearly, fixed blades were easier to make and could be made bigger and stronger for heavy work in everyday life. Even today, fixed blades would be the most common form of knife. Still, the guard would have been valuable in a small knife, able to be carried very discreetly, but suitable for relatively heavy use. The guard provides a critical margin of safety for the hand as tasks get heavier, such as butchering, or any task where the handle might get slippery and the hand could slide out onto the blade, including defensive use in fights.

It also makes sense that the swing guard would have been an early elaboration of basic folding knives, recalling the guard on both daggers and hunting knives. Several commentators think the dagger-like shape of the narrow spear point blade common in many swing guard knives recalls an Italian and or Spanish – a Mediterranean ancestry of these knives. Methods of forging knife steels were available after about 1740 (See Dewey Ferguson’s delightful short history of folding knives, 1970). I am in agreement with Mr. Punchard (2017); the swing guard knife had to be in the repertoire of major knife-making centers such as Solingen Germany, and Sheffield England, and all across Europe, well before the 1850s, when skilled workman from these centers helped populate the American knife industries through the latter half of the 19th century. Schatt & Morgan participated in that market, and their products provide the foundation for all current Queen Cutlery swing guard knives, as shown below.

While we see that the spear blade was offered as early as 1907, its social meaning with the guard had changed in the public eye, and knife makers responded. The spear blade was re-introduced in 1994 in only the premium Schatt & Morgan Annual Series. Beginning around 2001, a number of factory special orders (SFO) signaled interest in the spear blade. In 2013, the spear blade was back on a cataloged swing guard – the olive drab linen micarta (1LLM), perhaps the most “military-looking” Queen swing guard. It has been a recent theme in the group of Queen Special Projects (QSP 13 – 20). The traditional “Hunter” is undergoing a transformation toward “urban personal defense.” Again, the buying public is offered more choices.

These knives will probably remain less than best sellers in terms of units sold. Installing a guard means several extra parts and steps in making a knife, and the fit of components must be precise or the guard will wobble and not function well. Producing a swing guard takes a bit more time and requires a bit more skill of the maker. So, swing guards, already a large knife, are therefore often a bit more expensive than making a smaller, folding knife without a guard. Even in the modern era, some might be still be concerned that the size and prominent guard might cause the knife to be seen as “too aggressive” for politically correct social settings. For some, the folded guard may be seen as increasing risk of snagging the knife when pulling the knife from a pocket if in a hurry, or damage pockets, or interferes with an accustomed grip, or too big and heavy, and so on. The point is – These knives are not, and have not been, for everyone, for a long time. Thus, while many, many swing guard knives have been made, the number shrinks to a tiny percentage in comparison to the overall production of other folding knife patterns. Historical, highly functional, often graceful and decorated, relatively uncommon among knives – these are all considerations making swing guards a highly collectible knife.

Schatt & Morgan Production of Swing Guards

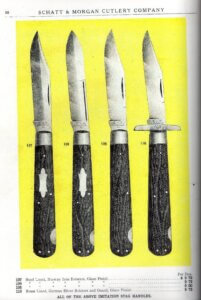

David Clark’s (2010) exact reproductions of the Schatt and Morgan catalogs for 1903 and 1907 provide a bedrock summary. In 1903, (Figure 1, page 29) two folding lock back patterns were offered – #116 with a swing guard, and #106 without a guard. In the 1907 catalog (Figure 2, page 90), the number of lock back knives has increased to four. The plain lock back knife, #106, now has grown – version #107 with a shield and polish, and #109 with a spear blade. A version of the #106 with a compass in the handle (#10, shown on page 91) is also listed as “discontinued.” The steel liners used in the versions of the #106, 107, 109, would make this a very heavy-duty knife.

The #116 swing guard lock back also still offered in 1907. Note that the earliest swing guard (1903) has a curved shape, and by 1907, this has already been replaced by a gradual rounded top for the guard. The clip blade is offered on four of five different models, reflecting the hunting heritage of the knife. They are clearly offered in both catalogs as “Hunting Knives.”

Of course, the company may have made other lockback knives. They may have made other changes in over 30 years of production of its swing guard, but that is another story. These few catalog knives provide the patterns and dies still in use today.

The 1907 Schatt & Morgan catalog contains 585 knife patterns (85 of them for “pearl” knives), so the four lockblade patterns represent substantially less than one percent of the company’s offerings. The one swing guard knife #116, would have faced competition from regular fixed blade hunting knives, as well as the other lockback, and necessarily, must have been a small part of the company’s sales volume.

Figure 1. Page 29, 1903, Lockbacks Schatt & Morgan Catalog, (David Clark, 2010). Notice slight difference in guard between Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2. Page 90, 1907 Lockbacks, Schatt & Morgan Catalog. (David Clark, 2010). These knives are shown “almost full size.”

Figure 3. Actual Schatt & Morgan lockbacks, about 120 years old. Only one Swing guard, Model #116, at far right, while three have just lock the blade. Clip blades predominate as hunting knives. And the spear blade, #109, is by far the rarest of this set. I have seen only one knife of this pattern in 18 years of collecting. All frames are the same at 4.5” closed.

Figure 4. A swing guard knife offered by Shatt & Morgan before 1907 with a compass embedded in the handle. The 1907 catalog shows the knife as “Discontinued” on page 91. We do not know if this knife was originally offered in “candystripe” celluloid, or if someone a long time ago customized the knife. (Because of the celluloid’s risk of “degassing” which will ruin the knife or nearly knives, this example is stored in a vacuumed sealed bag and stored away from other knives which does hurt the image somewhat – Sorry. Again, a very rare knife).

Queen in the 1990s, tried to source small compasses to attach to their new re-introduction of swing guards, but they could not find a supplier. An original of this version might be the most valuable of the original Schatt & Morgans swing guard knives. Especially in a bone handled version could be found. An original would be well embedded into the handle and not protrude.

Queen City and Queen Cutlery Production of Swing Guards, 1922-1991.

Queen City, from 1922 through reorganization at the end of World War II never produced a catalog and no labeled swing guard knives that we know of. A very practical company who knew their clientele, they only offered a lockback knife called the #36, that is the same pattern as the more popular #106 of the Schatt & Morgan era. Figure 5 shows Queen City offerings and Queen Cutlery follow-up knives through 1983. Comparing the first knife to the remaining nine, it is easy to see how this knife was once a swing guard, and was the patterns for the lockbacks that followed it.

Figure 5. Queen City and Queen Cutlery #36 lockbacks, 1922-1983

In Figure 5, From left to right: first, A Schatt & Morgan era swing guard (#116, 1907-1931); second, an Amber #36 with Queen City straight line tang stamp, long pull, saber ground clip blade; Third, A Queen Cutlery sandblasted blade etch “Q between Queen and Cutlery”, no tang stamp, Rogers Bone handles (post WWII). Fourth, a Model #36 with Winterbottom bone handles and high Carbon blade with a “big Q” tang stamp (1950-1953; Fifth, a bone handled clip blade, no etch, Qsteel tang stamp (1954 -1957); Sixth, a bone handled clip blade with Queen #36 blade etch and QSteel tang stamp (1958-60); Seventh, a bone handled clip blade with Queen #36 blade etch, and no tang stamp (1961-1971); Eighth, a bone handled #36 with a Queen Cutlery Titusville PA blade etch, no tang stamp (early 1970s); ninth, #36, Queen Cutlery Titusville PA blade etch and no tang stamp (late 1970s), and tenth, at the far right, number ten, a re-issue of the “Old Pattern Lock Back”, 1983 (edition of 700) with Winterbottom bone handles, commemorative blade etch, and sold with a clamshell box. (Photo courtesy of Fred and Linda Fisher).

Figure 6. An “Old-fashioned Lockback,” sold as #6155 in 1983 – the far right knife in Figure 5, in an edition of 700, with a black clamshell box. It was clearly identical to the #36 which Queen and Queen City made, but was not seen again until 1992, when the swing guard model reappeared.

After the second World War, the #36 was re-introduced by Queen in 1950 (Catalog 85) and continued in the catalog through 1965. (see http://queencutlery.com/uploads/Model_36__47-2013__7-19-2015.pdf)

In all catalog listings, the One Blade Lock Pattern #36, is shown as being offered in “high carbon steel” throughout each catalog describing it. The Figure 5 above, documents that a great many of these knives were made in stainless steel – (number #5 through 10 in Figure 5, above were probably all stainless). The way the #36 was handled in developing catalogs, suggests this knife was not a large share of sales (like the #106, and #116 before it). In the first six catalogs, (‘50, ‘52,’53, ‘54, ‘55, ‘56), we can see that the same photograph was for used for each one by examining the background, and details of the Winterbottom bone handle. Then, in the next four catalogs (‘59,’60, ‘63, ‘65), it seems the same photo was still used again, but modified by adding a “Queen Steel #36” blade etch to the blade in the picture. Sometime early in the 50s, stainless steel was adopted for this knife, and had been accepted enough that the catalog sales people wanted to make the point by 1959. Note, that even though the item description had been re-typeset, without changing the text, and still says “high carbon” steel. Queen may have simply offered both steels depending on customer order, through the years of producing the knife, and not given too much attention to changing the catalogs.

Review of Sargent (2008) and Queen Cutlery primary catalogs from 1947 through 1991, for swing guard knives for the entire period shows NO swing guards were produced by Queen until the re-introduction of the Schatt an Morgan line in 1991. .

The modern Queen swing guard knife was adapted from the pattern dies for the #106, and #36, held from purchasing the Schatt & Morgan factory at auction in 1933. Adding the mounting hole through the base of the blade, producing the two guards, setting the pin that mounts the guard, and buffing the bolster a bit differently were required (Personal communications, Frederick Fisher, Jenny Moore). Note that Queen Cutlery under the Daniels Family has re-issued this old Queen #36 pattern, including it as an option under some versions of model #1L.

Swing Guard Knives and Social History

It is clear that early in the 20th century, Case called its swing guard “The Switchblade,” after the Italian stiletto being carried by many immigrants. But American sentiment drifted away from the swing guard as its identity got wrapped up in “stiletto,” and association with organized crime and youthful gang violence (see for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stiletto). Many laws were enacted to reduce access to automatic knives in the 1950s, culminating in the U.S. Switchblade law of 1958.

Queen’s experience with the original model #25 Jet was like other companies – newly illegal inventory had to be destroyed. See our earlier article: The-jet-4-19-2022.pdf (secureserver.net). Big lock back folding knives became a small market for several decades, until the approximately the early 1980’s when the Buck 110 made large sales and demonstrated that consumers wanted substantial knives that had locking blades. Queen responded (Think of Queen’s Hawk Series and Rawhide Series), as did other American cutlery firms. And finally, in 1992, Queen Cutlery brought back the swing guard, after searching for early Schatt & Morgan patterns that been out of production. (Please see our references to the development of Queen “collector knives” in the mid ‘80s and ‘90s (Lago, Krauss, and Fisher, 2023). In keeping with history, they focused only on clip point blades in the first issues.

While we see that the spear blade was offered as early as 1907, its social meaning with the guard had changed in the public eye, and knife makers responded. The spear blade was re-introduced in 1994 in only the premium Schatt & Morgan Annual Series. Beginning around 2001, a number of factory special orders (SFO) by Clarence Risner sold out completely and signaled interest in the spear blade on swing guards. In 2013, the spear blade was back on a cataloged swing guard – the olive drab linen micarta (1LLM), perhaps the most “military-looking” Queen swing guard. Spear blades have been a recent theme in the group of Queen Special Projects (see QSP 13 – 20 in our Excel file on Swing guards). The traditional “Hunter” is undergoing a transformation toward “urban personal defense.” The buying public is offered more choices.

These knives will probably remain desirable but less than “best sellers.” Installing a guard means several extra parts and steps in making a knife, and the fit of components must be precise or the guard will wobble and not function well. Producing a swing guard takes a bit more time and requires a bit more skill of the maker. So, swing guards, already a large knife, are therefore often a bit more expensive than making a folding knife without a guard. Even in the modern era, some might be still be concerned that the size and prominent guard might cause the knife to be seen as “too aggressive” for politically correct social settings. For some, the folded guard may be seen as increasing risk of snagging the knife when pulling the knife from a pocket, or damage pockets, or interfere with an accustomed grip, or too big and heavy, and so on. The point is – These knives are not, and have not been, for everyone, for a long time.

Still, Schatt & Morgan’s, and Queen’s experience with this pattern has shown that some collectors really like this knife and there has been a market for this knife from the very earliest days of the 2oth Century, though with slippage in the late 1950s and 1960s when the “guard” was viewed negatively. But gradually, in the 1980s, when lockbacks returned to a little bit more favor, Queen would re-introduce the pattern. We will follow that newer history in two articles -one with Queen’s catalog knives and “special projects,” and then with a final article that discusses the patterns great favor with Special Factory orders (SFO) who provided over half of the swing guards Queen produced. And, finally the Excel file will be available to help manage the large number of versions of this pattern produced by Queen.

NOTE: This is a second edition article, revised from a 2019 version but, as always, we appreciate suggestion for addition or critiques that will help us improve coverage of this topic. Thank you.

References

The-jet-4-19-2022.pdf (secureserver.net)

Fisher, Frederick (20013) Personal communication on #36 and 1L Queen Swing guard.

Lago, Krauss & Fisher (2023). Collector Knives for Queen Cutlery & Servotronics, 1985 -1987. – Queen Cutlery Guide

Lago, Krauss & Fisher (2023. Collector Knives for Queen Cutlery & Servotronics, 1988 -1998. – Queen Cutlery Guide

Moore, Jenny (2013) Personal communication on Making Queen Swing guard pattern

QueenCutleryguide.com (2019). Queen Production of Model 1. Model-1-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

QueenCutlerygude.com (2019). Queen production of #36. Model-36-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Sargent J. (2008). American Premium Guide to Knives and Razors: Identification and Value Guide (7th Edition). (pages 423 – 503).