Queen Cutlery Collector Knives, 1980s -1984.

Dan Lago, David Krauss, Fred Fisher, 2-10-2023

Introduction

Queen entered into the 1980s with a decade of substantial efforts to modernize their cutlery offerings and knife-making process (please see our earlier article on this topic: Queen-Cutlery-Servotronics-early-experience-with-collector-knives-1970s.-1-28-2021.pdf (secureservercdn.net) (Lago, Krauss & Fisher, 2021, in references). However, the company was not yet ready to commit themselves completely in the collector market. It’s likely there was no specific multi-year marketing plan. For that reason, we have divided the 1980s into three articles, the early 1980s through 1984, when economic catastrophe occurred, then recovery 1985-1987, and continued success in 1988-1991, since they are dramatically different stories.

Queen’s improvements at the very end of the 1970s, started to pay off in 1981, with a major success in the National Knife Collectors Association, the “Bullhead” (Lago, 2021).

Figure 1. The 1981 “NCKA “bullhead” with its etched blade, stag handle, shield and descriptive tang stamp was a strong demonstration that Queen was ready to produce collector grade knives. (Internet photo)

Two key points for the story of Queen collector knives emerge from this one knife.

A.) Queen produced 12,000 knives with only 83 being returned by the NKCA – an incredible 0.007 return rate!;

B.) This success launched Queen as a frequent provider of NKCA collector knives over 30 years and caused many other knife producers to consider giving special jobs to Queen Cutlery (See Carl Bradshaw’s summary of Queen NKCA knives on our site and in the References).

In many ways, the successes in the 1980s began in the middle 1970s when in 1975, William (Bill) L. Howard, a young man just out of high school at the time, joined Queen to work in the hafting department. We also see Bill Howard working in the grinding room in 1977 (Figure 2) and then working in the stamping and forming department (the “Press” room). He joined the U.S. Air Force at the end of the decade but returned to the grinding room as foreman by 1982, following the company tradition of gaining strength as a cutler who had skill in each of the company’s departments. We maintain his tenure there is largely responsible for Queen’s ability to produce the finest of collector knives during the 1990s through 2007.

Like most young people, his early work was “just a job,” for him. But working in the Press room and seeing how the basic steps of making the parts of a knife were done, sparked what would become a lifelong passion for Howard. Most of his training was “on the job,” provided by other workers in each department as he moved from assignment to the next assignment. His skill in each cutlery job was built by repeating the same task until he mastered it. Many times, there was little supervision. As an example, blades for the #39 hunter were delivered in large wooden trays which held over 150 blades per tray. The trays, about 2″ tall, were stacked beside the big grinding wheel from floor to over 4 feet high – roughly 3,600 blades, each needed the same grinding operation. If a blade was not properly ground and a problem was noticed in the next phase of knife production, he had to redo those steps all over again and repair (or waste) the parts. He learned by a number of skills by trial and error as there was no oversight of the blades he finished.

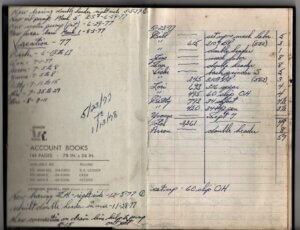

Overall, the factory had very little quality control or useful supervision in his early years and at any time, he could be reassigned to another department. Daily tallies of work by each employee were used all through the 1970s and early 1980s by Queen Cutlery in every department. Speed in completing tasks was demanded (“parts” divided by “time” – 3,361 parts by 57 hours, as in Figure 2). The “time and motion studies” Queen favored measure quantity, but did not emphasize the quality of specific completed parts. Quantity was valued over quality.

Figure 2. Grinding room record book from Queen Cutlery, 1977. (5.25″ x 7.75″, opening page, 5-23-1977). “Bill” Howard is shown doing his regular work, “set up grinding machine labor” for a particular blade. (© Dan Lago)

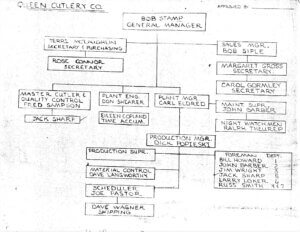

A Queen Organizational Chart for the leadership of the company from 1982 is displayed in Figure 3. Originally, this document included a two-page complete list of persons filling certain jobs at the each of eight Departments. We only include the names of leaders here who helped engineer the company’s survival in late 1970s. We feel their names should be included in any history of those who helped the company transition from its history of making basic tools to a company that made high-quality collector knives. However, we honor the privacy of other 56 employees and do not include their names since their names and jobs were never public knowledge and their specific jobs may have changed over time. The following pages do include a description of the various departments with job titles to show the organization of the Factory in the early 1980’s period. Coincidentally, the descriptions below will give the reader some understanding of the process by which the pocketknives were actually assembled.

Figure 3. Queen leadership Organizational Chart, 1982. (© Dan Lago)

Dept 1. Stamping and Forming: There was a foreman, and Assistant foreman: to plan and supervise the work of the other 8 members. In, 1982 Bill Howard was serving as the foreman of this Department. Die Maker: make dies for stamping out specific knife parts. Six press operators, 2 each at levels #2, #3, and #4; Operate large presses with dies for steel blades, brass or nickel silver parts and manage the raw materials, steel and brass used for those operations. Spot welder: one man for die repairs or modifications. Set-up man: to place dies on presses for specific blade and handle components.

Dept. 2. Grinding room: Use large grindstones to shape blades. There was a foreman and assistant foreman, a compressed wheel operator, and a Nicholas grinder operator.

Dept. 3. Cover Room: Prepare handle scales, install shields. The job titles were Foreman and Assistant Foreman, marking scales (2 persons), Cutting covers (3 persons), Die Caster (1), Counter sinker (1).

Dept. 4. Blade Finishing: Use grinders with finer grits sanding belts to finish blade shapes. Foreman and Assistant Foreman, one Compressed wheel operator, One Polished Machine Operator, Four Double Header Grinder operators, two stone grinders.

Dept. 5. Assembly Department: Assembly of knife components in proper order and basic fit. Jobs were Foreman, Assembler (four persons), one spinner, one spring dresser and one repair man.

Dept. 6. Hafting Department: Complete attachment of blades to handles for final fit and function. Jobs were Foreman, Six qualified Hafters, four final adjusters, and two blade buffers.

Dept. 7. Finishing: Polish completed knives. Job titles included: one edge setter, two buffers, one honer, buffer, and engraver, one engraver, packer, and edge buffer, and one final inspector and cleaner.

Dept 8. Shipping and Receiving: Machine maintenance and cleaning. This department includes the name of one job title Display Maker, for assembling distributor-purchased knives permanently to various sizes of wooden displays. No other job titles are provided for the actual work of selecting and packaging knives for mail to customers, or for factory and machine cleaning.

As discussed in our previous article about the 1970s, there was a “lot of overhead” in this management team. They had meetings every morning that included managers, foremen and assistant foremen, and had to regularly communicate with the “absentee owners,” Servotronics management at Ontario knife Company (OKC) in Franklinville, NY. The excessive time for these meetings clearly took time away from knife production. In spite of all the management meetings and efficiency studies the result was little or no change in increasing the actual production of knives and despite those studies and meetings Queen would not be efficient enough to withstand the changes in economic conditions in the middle of the decade.

Knife Models in the 1980s. As discussed in the article on the 1970s, the Rawhide and Chipped Bark series were the mainstay catalog knives for the company through the entire decade. The Hawk Lockback series was also offered through the entire decade. (Search QueenCutleryguide.com under Catalog knives, under SERIES for summary of those knives).

By 1979, Queen’s two barlow special editions and the “Master Cutler Collection” had drawn attention to the company. Collector interest in stag handled knives was growing rapidly and many cutlery companies were developing stag offerings. Queen followed suit and produced the first folding stag catalog knives, the “Genuine Stag” Series beginning in 1980 through 1983 (see Figure 4). They sold well with massive stag handles, using patterns that had already been successful for Queen. Their blades were specially etched. It is very likely these knives were also produced in the 440C steel like all other the knives in their catalog.

Figure 4. Queen Cutlery “Genuine Stag Series,” very wide stag handles, 1980 -1983. The first stag handled knives and with different blade etches for each knife. Often these are found for very reasonable prices. (© Fred Fisher)

The “Old Fashioned lockback” (Figure 5) was part of this series, (#6155 in the Genuine Stag series) was an exact copy handled in old Winterbottom bone already in inventory, of a discontinued knife pattern (the much earlier Schatt & Morgan #106 and Queen Cutlery #36). This was the first time Queen returned to its early history to feature an “old” style knife. Looking back, this may have been part of a plan to “bring back” a prior knife, similar to the strategy used with the reintroduction of the earlier Schatt & Morgan brand from 1991 forward. The knife was presented in a darker clamshell box like the “Master Cutlers” (but in an edition of 700 rather than the larger 300o edition). Like the barlow knives this lockback was also issued with a prominent serial number on the mark-side bolster.

Figure 5. “Old Fashioned lockback”, 1983, edition of 700, in winterbottom bone, serialized bolster, and clamshell box (this knife as #6155). These knives have remained of strong interest to collectors. (Photo © Dan Lago)

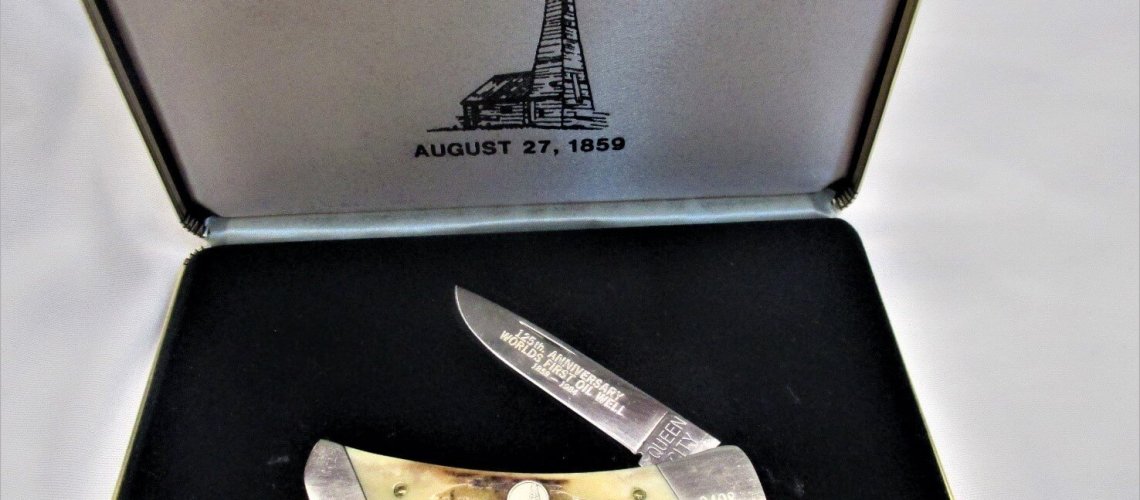

Four stag lockback knives, were produced in 1984, and these are among the last bright spots for the company in the early 1980s. Three of the knives were medium size lockback knives the same as the #6115 stag lockback in the “Genuine Stag” series. This knife was the same size as the Rawhide #4425, or Hawk series “Duck Hawk #1210”, and the medium Aluminum lockback (#6125), meaning four distinct levels of this popular knife were offered in the mid-1980s, along with the collector versions we profile. This is a fine example of Queen providing consumer choice and multiple knives at varying price points. However, the stag “Drake Well” version in an edition of 1500 and a black clamshell box (Figure 6) was by far the most popular.

Figure 6. The Drake Well Medium Stag lockback in a Black Clamshell box. The knife had a gold etch and for the first time used the early Queen City block lettering tang stamp on a modern knife. It also used a special shield showing the original Drake Well. (© Dan Lago)

A second identical stag handled knife, with the blade etch of “SHOT show, 1984” was given away as a premium at that major show, and a third, the “Cytemp” knife (edition of 150), was produced when the local Cyclops steel company changed its name. Both of these knives used different etches, tang stamps and shields. The Cytemp knife was offered a beautiful oak box with glass lid. Clearly, Queen was pushing hard to get the their basic modern lockback transformed to a beautiful collector knife.

Figure 7. The Small Stag lockback was the second Drake Well commemorative in 1984. This small lockback (the same size as #8845 Rawhide knife) was produced in an edition of 500. (NOTE: This knife can be distinguished from a very similar knife produced in 2000 because it shows the date 1984 on the top mark side bolster and 1859 on the lower bolster. It uses a different deep etch on the blade but the same tang stamp found on other lockbacks in the Hawk and Rawhide series of the 1980s.) (© Dan Lago)

These knives emphasized both Titusville history and the company’s interest in proving it could produce an array of quality choices for collectors interested in lockback knives in the 1980s. (The general interest in lockbacks likely originated with the introduction of now ubiquitous wood handled Buck 110 in 1964). These stag knives were all presented in very nice boxes and retain high value among collectors to this day.

Figure 8. Stag and Pearl 2-blade Copperhead knives, in a set of 500 with matched serial numbers with a unique one-time blade etch. See both P013, and S013 in the image above. Although it took almost 10 years for the Drake Well 1972 barlow to sell out, these 1984 knives never appeared in a catalog, but all Copperhead sets sold out before they were officially offered to the public, indicating a strong and growing interest in Queen collectable knives. (© Fred Fisher)

There were a few catalog knives added as well during this time, but catalog knives are not the focus of this piece, we simply mention them in passing. Two were the buttonlock hunting knives (44B and 410B) and another was the boot knife hunter (#3505) a modern-looking full-tang knife that required a manual double grind on both sides of the dagger blade with a large integral guard and handle in stabilized black wood. We will discuss these pieces another time.

Economic Collapse in late 1984.

Instead, we shift to an economic downturn for the company and the huge lay-offs which characterized the mid 80s, yet somehow finally paved the way for Queen’s greatest successes; the niche market of making collector knives. Unfortunately, the generally good economy of the time was not experienced by Queen Cutlery (See U.S. Economy, 1980). For an example we can say that in over 40 years of dedicated collectors searching and collecting Queen literature the only years with absolutely no sales fliers or catalogs found were 1985 and 1986, despite beginning the 1980s with their first annual color catalogs and fliers (see below).

There have been no documented reasons found for the “no catalog decisions” made by Queen’s owner Servotronics and the Ontario Knife company management. Some with an understanding of the time have suggested that loss of Government contracts for both Servotronics and Ontario Knife companies were to blame. Some believe that Federal contracts and failures in military and kitchen knife sales in Africa were to blame. Others have blamed high overhead costs for management and increases in customers’ concerns about the diminished quality of knives that Queen was producing. There was also much tougher competition in the growing collector market and that was also an obvious factor. Domestic cutlery companies like Case, Camillus, and Buck were producing new, desirable knives. And many collectors became enthused with extremely high quality, but expensive knives made in Solingen, Germany by Olbertz cutlery, for American entrepreneurs such as Frank Buster’s “Fight’n Rooster” brand, and Charlie Dorton’s “Bulldog” brand (first generation).

At Queen a number of managers were let go or permanently laid-off in late 1984. Robert Stamp, General Manager, was removed first. Then Carl Eldred (Plant Manager), Fred Sampson, (Master Cutler), and finally Robert Siple, (Sales Manager) followed. Looking back at Figure 2, the Titusville Cutlery management had been decapitated. Servotronics centralized all decision making to the Franklinville, NY offices of Ontario knives. Don Shearer was appointed the Queen plant manager at Titusville.

In 1982 there had been 56 workers on the floor, well documented by the 1982 organizational charts (Figure 3, above). The number of staff position was dramatically reduced from 56 to just a few workers in 1985, perhaps less than half a dozen full time employees left on the factory floor. It’s unclear what office staff remained, but overall the staff reduction was approximately 90% or more, a devastating downturn. Of course, output needed for recovery was seriously reduced. Bill Howard was retained but had to move from multiple machine stations to finish tasks for a set of knives. There was not enough work to keep the few employees busy.

The only good news is that when Queen hit bottom in the mid-1980s, Servotronics interceded and kept the company from closing, covering some payroll and operating expenses, and consolidating some administrative positions by moving them to the OKC headquarters in Franklinville, New York. There is no documentation of the details of Federal contracts (a success which can likely be attributed to either Servotronics or Don Shearer). Queen’s remaining workers made many knives under Federal contracts, especially Military Utility Multi-Tool knives (Figure 9), and medium stockman (Model #9), electrician knives (model #40 – till 1981), and hawkbill pruning knives (model #1W). The parts for these knives were blanked out in the Ontario knife factory, but the assembly was completed in Titusville. They did help to keep the company afloat.

Figure 9. (A Queen or perhaps Servotronics-assisted knife) Federal contracts resulted in a great many “Military utility multi tool knife” that helped “Keep the lights on” at Queen Cutlery in the middle 1980’s. At the same time, these very utilitarian knives demonstrate how low the company’s aspirations had fallen compared to the beautiful stag knives produced only a few years before. (© Dan Lago)

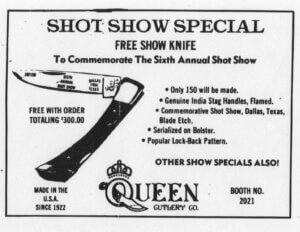

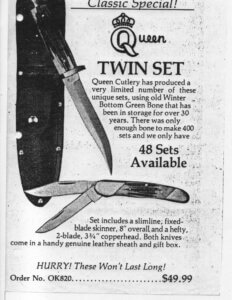

To provide a sense of how financially strapped the company was, the following three illustrations show advertising pieces from this time. Figure 10 shows a set of Rawhide knives on the cover of 1980 catalog that featured many colored pages. This cover also shows Rawhide knives specially selected for much more handle variation than usually seen in the series and are shown in a nicely prepared snowy outdoor scene. Then, notice the difference in figures 11 and 12, in what seem to be copies of xeroxed black and white images which were produced during the difficult time of 1984. Figure 11, shows a poor image of the SHOT show special lockback knife while figure 12, displays a green winterbottom twin set hunting knives. Both advertisements of these pieces would have been greatly enhanced by color! Today these particular knives are greatly sought after by collectors. But, they seemed to not catch people’s attention at the time. It’s likely that the poor ad presentations hindered sales.

Figure 10. Front cover of the Queen 1980 catalog. (© Dan Lago)

Figure 11. Black and white advertisement of the 1984 “Shot Show Knife.” Compare its image with the very similar knife shown in Figure 6, above. (© Dan Lago)

Figure 12. Another black and white 1984 Xerox-processed advertisement for a knife set that was never shown in any other ads during a time of major reduced operating funds for Queen Cutlery, although in very rare “Green Winterbottom bone” it still commands high interest and value among Queen collectors. (© Dan Lago)

Conclusion and summary

Queen Cutlery began the 1980s with a management team that had modernized the company’s offerings in the late 1970s’ and was oriented, particularly in the sales department, to seek opportunities to produce fine collector knives for that emerging market. They had produced some “winners” in the NKCA collector knives and in a number of their own products. Their staff included skilled people who could reliably complete stag-handled knives of very good quality and they produced a variety of knives that have retained their value over a 40-year period. However, during this time period the parent company, Servotronics, seemed chronically cautious and a bit unsure as to what Queen should be making – they place a heavy emphasis on their new lines of catalog knives. Even though its owner, Servotronics seemed somewhat willing to build on the foundation built in the early 1980s”, Queen suffered a major economic collapse in later 1984 that resulted in losing most of their on-site management, the vast majority of their skilled workmen, and any claim they had at the time to the collector market.

Queen was only able to remain viable thanks to the support from Servotronics (via OKC) and their joint ability to secure Federal contracts for military knives, some of which they channeled to the Queen factory to avoid bankruptcy, and increasing reliance on collaborating with other cutlery companies. In a strange way, this time of no substantial real business allowed Don Shearer to task Bill Howard to pursue other useful sources in the industry and learn more about the materials (old dies, parts, etc.) that were still stored in the factory. These older materials would prove invaluable when Queen decided to bring back older patterns and the Schatt & Morgan name. This orientation toward revitalizing the company’s predecessor’s quality and traditional patterns provided an opportunity for Queen to rise to the top of the cutleries producing collector knives in the last half of the 1980s, and the re-emergence of the Schatt & Morgan brand by 1991. We will tackle that time period in our next two articles, “Collector Knives for Queen Cutlery & Servotronics, 1985 -1997, and 1988-1991.

As always, if you feel there are errors, omissions, or suggestions for improving this article, please contact us with your ideas or critiques.

References.

Bradshaw, Carl, 2018 Queen-Produced-Knives-for-NKCA.pdf (secureservercdn.net)

Krauss, David (2002). Schatt & Morgan sets 1991-2010. Knife World, Vol 36, no. 7, July, 2010, p. 1.

Lago, Daniel (2021) The-National-Knife-Collectors-Association-bullhead-1981-1-28-2021.pdf (myftpupload.com)

Lago, D., Krauss, D., & Fisher, F. (2021). Queen-Cutlery-Servotronics-early-experience-with-collector-knives-1970s.-1-28-2021.pdf (secureservercdn.net)

United States Economy – A Brief History – The 1980s (countrystudies.us)

Queen Cutlery Guide.com sites

Genuine-Bone-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Genuine-Stag-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)