Dan Lago, David Krauss, Fred Fisher, 5-15-23

Introduction

This is the fourth article in our series of Queen’s transition from a basic tool-making cutlery to a highly regarded maker of collector-grade cutlery. The first article covers 1972-1980, the second covers 1980-1984. The third article adds the years 1985-1987. This fourth article adds the years 1988-1998, when Queen, in collaboration with Charlie Dorton and Blue Grass Cutlery, produced the Case Classics line of collector knives and finally launched its own Schatt & Morgan premium line. We conclude with a summary of all four articles, showing how Queen after twenty years, had secured its reputation in the cutlery industry as a specialist creating collector grade knives.

The increasingly shorter time frames, covered in the last two articles provides evidence that a lot was happing at the end of the 1980s. As George Smith declared in discussing this history, “It seemed like it all happened at the same time.” A prime example is the John Primble, Winchester reproductions, discussed in the third article were also continued throughout the time covered in this piece, along with the Case Classics and the Schatt & Morgan Keystone knives and Queen’s own marked catalog knives. We also expand the time frame a bit to include the Press Room Fire in 1994, which significantly affected Queen for many years.

As Queen earned substantial revenue from Blue Grass Cutlery contracts, they also increased the skill sets of their labor force from earlier in the decade. This prompted them to look internally, and to begin to produce their own premium knives. They released two collector knives under their own mark in 1988, a #66 muskrat and a #32, 4-blade Congress, and both were labeled as the “66th year anniversary knives.” Both knives were housed in a small oak box with a Queen label in the upper left corner of the glass lid (first used in 1984, in the Cytemp stag lockback and already available in their inventory).

The muskrat was touted as the first time Queen did all the work on its own bone handles, the direct beneficiary of Bill Howard’s efforts to use a modified contemporary milling machine to jig Queen’s first bone. Although these knives did not sell all that well at the time of release, they were quite well made and clearly showed the benefits of working on the John Primble and Winchester knives with Charles Dorton. At that time Queen knives generally were not as well known for their quality and collector value then as they are now. Both of these knives are now valued by collectors for both their historical significance and their quality. It is quite probable that Queen executives were thinking about the initial mediocre sales of these knives when they began to develop a “cautious” approach to launching their own premium brand in the next few years.

Figure 1. the “Improved Muskrat” as the 66th Anniversary of Queen Knives, 1988, resting on top of Oak presentation box. Queen’s first knife with their own in-house bone handles. (© Fred and Linda Fisher).

Development of the Case Classic Line

Partnerships in business can be difficult to maintain over time. Consistent with the informal, interpersonal knife deals that characterized the cutlery subcontracting business at the time, a gradual tension developed between Dave Scott and Charlie Dorton, and between Queen Cutlery and Blue Grass Cutlery (from Queen’s perspective). Dorton’s purchase of sample knife parts made by Queen became an issue. Dave Scott objected, maintaining that he owned the dies and ordered Queen not to make parts for anyone else using his dies. And there was apparently some controversy over who owned the older Schatt & Morgan dies that also might be used for other projects.

Also, by our understanding, as demand for the Winchester knives grew, George Smith and Dave Scott insisted several times that Queen give them reduced wholesale prices for each knife, since Blue Grass was also supplying some of the bone used in the knives. Queen’s staff on the floor of the factory claimed they had to increase wholesale prices in order to keep the knife quality high and to add trained staff to complete the work in a timely way. And Queen was facing internal cost increases as we will see. There were persistent difficulties with Smith and Scott in setting wholesale prices. George Smith still recalls these negotiations saying, “We started at $13 dollars a knife and went up to $26 a knife, when we could only sell them ourselves for $30; There was no way to make money at those prices.” (George Smith, 2022). There was also disagreement over production of SFO knives for Moore Maker.

Queen, along with Charlie Dorton, started looking for other SFO alternatives. This was the context from Queen’s perspective, when Charles Dorton helped broker the most influential SFO project in Queen Cutlery’s history with Jim Parker, who was then President of Case Cutlery; the development of the Case Classics line. We have been unable to find detailed evidence of exactly how this deal was made.

James Parker was a major, if not controversial, entrepreneur in collector knives and he had known of Queen’s work since 1981, when the very popular Bullhead stag knife was made for the National Knife Collectors Association. Queen had produced a large edition with only a .007 rate of rejection (Lago, 2021). In 1987, as the new owner of Case Cutlery, Parker was pursuing the same idea as Charlie Dorton and Blue Grass Cutlery; making new “old-fashioned” knives of very high quality for the collector market. He realized that though most collectors favored the appearance of older knives, they did not have the time to find the rare old knives, or the money to afford them, especially with the well-known CASE cachet.

Based on the appearance and the quality of the Winchester and John Primble knives, and knowing that Queen Cutlery, with Dorton’s involvement, was making the knives, Parker turned to Queen and Dorton to design and build the knives, and though Parker owned the Case Classic line of knives and had great resources for marketing, he turned to Blue Grass Cutlery to distribute them. It is very easy to imagine Charlie Dorton telling Parker, “Queen is already making these great knives in a traditional way and they have the tooling you need. We will use Blue Grass for distributing but I will be designing the knives for this project”! Although Blue Grass Cutlery was still involved in distributing and funding, their ability to influence the actual knife making was reduced, since Parker would deal directly with Dorton and Bill Howard at Queen on those decisions. However, Blue Grass Cutlery would still benefit financially as the sole distributor for what was very likely to be a very significant project for American-made collector knives from the most prominent historical cutlery manufacturer in the nation in the highly valued Case name.

Case did have some old tooling in their own shop, but not for many desirable patterns. While the details are hidden within private corporate files, it seems Case made the #88 four-blade Congress and perhaps a few other patterns including the gunboat (“three-blade canoe”) and the “Saddlehorn” using their own tooling https://www.allaboutpocketknives.com/content/knife-manufacturer-specific-research/case-classic-knife-reference-guide/. Queen and Dorton made most of the decisions about the 36 or so other patterns and then produced the knives at Queen. Blue Grass Cutlery had the contract to distribute the knives, even the knife boxes indicated that they made as well as produced the knives (see boxes on Figure 3 and 7.)

Figure 2. A Case Classic split backspring whittler in red banana bone and showing one of the many historical names of the Case Cutlery company on the blade etch. (Courtesy of SharpShinyknives on Allaboutpocketknives.com easily found under “Case Classics” brand with many other quality pocketknives as well for sale on the site. Used by permission.)

Parker and Dorton also emphasized designing a pattern with many variations. This resulted in many small editions of a given knife. With several different handle materials, blades, etches, or shields available, so that collectors would be encouraged to buy multiple, similar knives (as shown in two whittlers in Figures 2 and 3). In the figures for this section, you can see some of the variety of shields used in the Case Classics line.

Figure 3. A Case Classic three-backspring whittler in Burnt Yellow Rogers Bone. This knife was very difficult to produce since the three springs had to be perfectly straight to allow the knife to function well. The side of the box shows how Blue Grass Cutlery kept its prominent role in the Case Classics line clearly visible. This knife was made later in the series as shown by the newer box used. (Courtesy of SharpShinyknives on Allaboutpocketknives.com, easily found under “Case Classics” brand. Used by permission.)

In 1988, a poster was made displaying the first six knives of the Case Classics series, and the collectors’ interest and purchases were very gratifying, and therefore followed immediately by many more patterns through 1998. Blue Grass had produced a number of smaller 8.5” x 11” posters for many of the knives in the Winchester Black Box series (though they are rarely seen today) and probably played a critical role in the large poster introducing the Case Classics.

While Parker’s role at Case did not last, the Case Classics line was extended through 1998 with subsequent owners (Tim Scott, 2023).

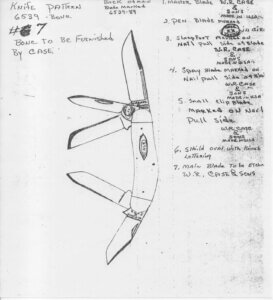

Figure 4. Internal Queen drawing by Charlie Dorton for Case Classic #6539 from 1989, with notations for staff on tang and etch locations on blades, and showing swedge lines as dark upper edges. He did a similar drawing for each version -100s of such drawings altogether. (Samples of these drawings were also found in the Titusville factory during the bankruptcy sale of Queen Cutlery Company in 2018.) Note the collaboration on source of bone for this particular knife directly from Case inventories.

The overall result of their efforts was a fantastic variety of extremely high-quality knives that were much like some of the old vintage patterns of the past. It is said that over 66,000 high quality knives were prepared just for the Case Classics by Queen Cutlery, and remain one of their most sought-after series of knives. They continue to command higher prices than any other Queen-labeled knives of the time.

We thank Frank Powers for giving us permission to share a few examples of Case Classics from his website: Franksclassicknives.com, under the “Case Classic” heading, located at 1923 Utah Mountain Rd., Waynesville, NC. 28785.

Figure 5. A Case Classic two-blade Elephant Toe #62050 in jigged yellow bone. Note the gold etch of dueling elephants and the bomb shield. An edition of 9. (Franksclassicknives.com. Used with permission.)

While these knives were for sale at the time of preparing this article, we do not list prices for each knife, but only say they ranged in price from $500 to $1,350 each. If you happen to find them for sale again, they will probably cost more! It is not hard to see why these knives have retained collector interest and have greatly increased in value. Made just before and after Queen introduced its own Schatt & Morgan Series in 1991, it is clear these knives gave a huge boost to their new line and solidified Queen’s reputation among collectors.

Figure 6. A Case Classic swing guard “Cheetah” #61011 ½ in genuine Heart Abalone in an edition of 10. (Franksclassicknives.com. Used with permission.)

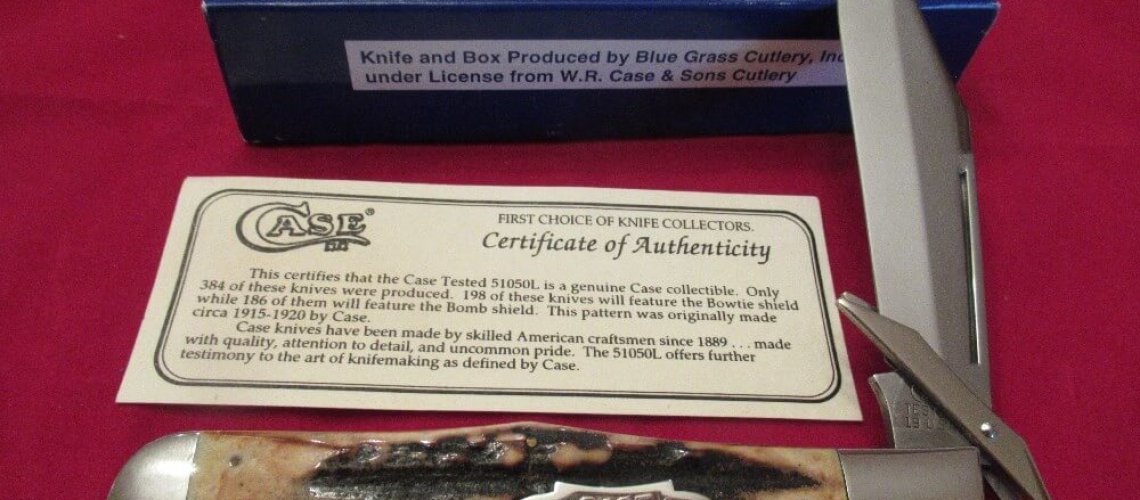

Figure 7. A Case Classic Large Swell Center swing guard hunting knife, 51050L. Bill Howard at Queen Cutlery in Titusville, PA made the tooling for this knife. Franksclassicknives.com. Used with permission.

It is interesting to note, James Parker’s Case Classics were perhaps not enough to save Case from entering a bankruptcy re-organization and sale shortly after the Case Classic project was marketed. Case may have paid a higher than expected price for having the knives produced outside their shop, which benefited of both Blue Grass and Queen. So, the economics of the undertaking turned out to have been less successful for some of the principals than others. The knives themselves remain a joy to collectors. Case began the process of bankruptcy and sale in 1990 (Knife Talk: The History of W. R. Case & Sons and Related Companies – Part 1 (knifetalkin.blogspot.com).

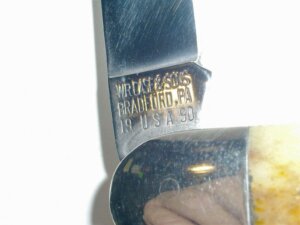

At Blue Grass cutlery’s urging, Queen Cutlery also made a large sleeveboard pattern with Winchester etched blade on the mark side and Case tang stamp on the pile side. Two photos are shown in Figures 8 and 9, with the Winchester blade etch in Figure 8, and Case tang stamp (1990) on the pile side. This SFO knife is rarely seen, but in a sense this knife perfectly describes the relationship between the three companies in 1988 through 1992. So, although there were disagreements between Blue Grass Cutlery and the Queen Cutlery company, those issues did not appear to impact the quality of knives that Queen produced during this time. Because quality knives were made available to the knife-buying public both companies found profitable ways continue the collaboration for many more years.

Figure 8. Large sleeveboard knife with Winchester blade etch, but with Case tang stamp on the pile side (see Figure 9) commissioned by Blue Grass Cutlery (for their Winchester brand) in partnership with Case Cutlery, but made by Queen Cutlery. Dated 1990.

Figure 9. Same large sleeveboard shown in Figure 8, but with Case tang stamp on the pile side. (Both Blue Grass Cutlery and Queen Cutlery relished the idea of a public connection with the great Case Cutlery company name.)

Throughout this period Queen still produced wood handled “rawhide” series, and the “Chipped Bark” Delrin series through the entire decade of the 1980s – maintaining their practical tool-oriented production of solid knives that were hafted with less expensive handle materials. Queen did introduce a “Genuine Bone” series (five small Queen patterns – small lockback, senator pen, sleeveboard pen, jack, and peanut with new model numbers) that did appear in Queen catalogs in 1987 – 1991, though without much fanfare.

Queen salesmen did note that the premium SFO knives sold very well and at higher price-points than Queen’s usual line of knives and they transmitted their findings to management at Queen and Servotronics. However, it is likely that the real impetus for Queen adding premium quality knives to its line-up came from the floor of the factory itself; the team of workers and supervisors who had gained skill and strong experience in the John Primbles, Winchesters, and Case Classics, and whose SFO work had actually saved the company. They were making high quality knives and wanted to put their own name on premium collector knives at last.

The Queen workers on the floor at this time had developed the additional skills, and the abilities to shift from one version of a knife to another efficiently and precisely, and of course more workers were hired to complete the work. These Blue Grass and Case contracts were a huge boost for Queen Cutlery and some have said that the payments from Blue Grass produced more funds at the end of the 1980s. Those SFO contracts might also explain the years-long run of both the Chipped Bark and Rawhide “user” series found in Queen’s own catalogs. Queen had been focusing its attention on producing high-level collectable knives for others. Now, the stage was set for Queen to focus on its own “old, higher – quality knives.”

Knife Collector Club “Custom” Knives

We should also note here that at the end of the 1980s knife clubs were growing in number and membership around the country. A few cutlery companies were supplying these club knives. Queen was able to tap into this market, using either existing inventory or extra parts they had from their SFO business. A blade or other parts of an “over-run” could be repurposed with small change, such as a blade or bolster etch, into a very cost effective “special” club knife, creating an additional niche for collectable knives, and additional revenue for the company. This ancillary part of collector knives was starting to get stronger, well ahead of the plan to market over-run Schatt & Morgan knives to knife clubs in the 1990s. Figure 10, shows an example of this strategy using the widely sold, but fairly workman-like #4225 Rawhide medium lockback knife. With the addition of a deep blade etch, bolster engraving, and a serial number on the butt bolster, it became a “custom club knife” This otherwise good quality yet basically unremarkable knife was released in 1987, the same year the Winchester reproductions were launched. Queen salesmen were increasingly looking for this kind of business, since the Queen facility had become more skilled and efficient in moving from one contract to another.

Figure 10. A 1987, SFO club knife of the #4225 Rawhide lockback, with a very solid deep blade etch and double bolster engraving, considerable accessorizing of a basic good quality working knife to sell another 100 knives. A side-effect of this collector market, is small changes for a club that made many unique variations of popular knife patterns that resonated with certain collectors.

Queen Launches its Own Schatt & Morgan Line

In 1990, two years after the Case Classic line was started, Queen decided to apply this “collectors want very nice old-time knives,” approach to their own history. They had greatly recovered from the corporate disaster of 1984-86 through the strong new direction laid out by success by the Titusville staff through collaboration with well-known figures in the collector knife market noted above. Some key members of the Queen staff, principally Bill Howard, had learned to use the company’s old tooling and dies much more effectively and make new tooling had discovered that with the improved skills and quality standards learned the in preceding few years, could now be turned into desirable products. Don Shearer, the plant manager had supported these innovations and they would pay off. These same key staff had learned the hard lessons of what was required to consistently build high quality knives that could be sold at higher prices and they were training staff to meet those criteria.

Around 1986, Servotronics promoted John Wyllie to President of both Ontario Knife Company and Queen Cutlery Company. He worked out of the Franklinville, NY, offices and placed a very high priority on increasing Queen’s profitability and its status within Servotronics management in Buffalo, NY. Wyllie and Dick Hilligus (Sales Manager at both Ontario Knife Company and Queen Cutlery at the time) felt that they could chart a new course with less reliance on Blue Grass Cutlery. Don Shearer and Dick Hilligus had weekly meetings in Titusville and agreed to have Bill Howard move forward with producing some drawings for the new line of knives. John Wyllie agreed and Bill began producing prototypes for Servotronics executives to consider. It is no longer clear who specifically first said “Lets reintroduce Schatt & Morgan,” but Bill Howard and local management were confident that this would be a wise decision given the acceptance of the Case Classic line. Finally, in 1990 the company decided to move ahead with a Schatt & Morgan series. It was a cautious decision, based on producing only a few knife patterns per year, with a plan to refine them each year and keep the line “fresh” for customers. This was unlike the strategy that Blue Grass and Case/Parker had used in making a huge investment in many knives and then holding them back until the demand grew. The Schatt & Morgan knives could be purchased individually, or as a complete yearly set, which included a glass and wood display case. At Queen, the hope was that collectors would support a yearly series of premium knives for many years.

Dick Hilligus traveled around the country, meeting with a variety of Queen Collectors, and he privately announced to them that the company would start its own line of premium knives, producing only a few patterns in limited numbers each year; a cautious approach. Hilligus asked these collectors for suggestions of patterns to include. There was quick agreement on adding early models from Schatt & Morgan’s history. For example, swing guard knives, Doctor knives, whittlers, and English jacks (abandoning the older name of “farmer jacks”). A scout knife was later added to the wish list. As far as we know, this was the first time any Servotronics executive had actually reached out to knife collectors. It was a very helpful, if unusual step in launching the Schatt & Morgan Series. They hit several homeruns in picking patterns that collectors were very happy with.

Even though the very old Schatt & Morgan dies/tooling was not heavily used in preparing the series, there was a small piece of old brass about 4” by 5” that someone in the factory had pinned old knife shields onto in the distant past. Among them were a number of Keystone shields to fit different sized knives (per Bill Howard, 2023). Coincidentally, as Queen staff met about this matter, they looked out the window, across Chestnut Street, and noted the critical Keystone holding the arch above the Press Room door. Even though the series was planned as a national release, they liked the symbolism of a shield for the knives based on the company’s history. (Even in the American Revolution, Pennsylvania was called the Keystone state, since it and Philadelphia were essential in holding the colonies together.)

Figure 11. The keystone over the bricked up original door to the Queen Cutlery press room on Chestnut Street in Titusville, PA. (Photo taken in 2023 after extensive remodeling by the “Ribbon Factory”, the current owner, which eliminated the earlier door.)

Queen did not manufacture the bone handles for the Schatt & Morgan reintroductions themselves. Instead, they developed new relationships with Culpepper Company, a niche industry started by David Culpepper in 1976, that produces natural handle materials for knives. David and Joe Culpepper were very interested in Bill Howard’s work with bone scales and were ready and willing to provide unique bone for the Schatt and Morgan Keystone series and greatly expanded their business (Culpepper & Co. — Fifty Fifty Productions). The first bone in the series was not specially named, but was very traditionally cut and dyed (eventually collectors came to call it “Honey bone”). The second year, a red jigged bone was dyed by Queen and was very striking. It was immediately seized by knife collector clubs, providing another market for special annual premium Schatt & Morgan knives. “Winterbottom bone” was used the third year and was the first named bone, most likely due to the Winterbottom factory’s historical long-term connection with Queen. It was initially provided in white, but to achieve a more traditional look was eventually painted before finishing. The Fourth year featured bright orange “corncob bone” and was the first bone to be radiused across it surface to provide a very comfortable and traditional feel. Most bone after that was carefully named. The innovations in the bone handles were a critical part of the success of the series, in our opinion.

In 1991, after almost a year of preparation, Queen did introduce its own collector line (which later came to be called the “Keystone Series”), and the journey from “tools” to “collector knives” was finally completed. Collectors as well as the cutlery press were immediately impressed and enthusiastically welcomed the “new” line of “old style” knives. The nascent Schatt & Morgan series was the outcome of an almost 20-year journey for the company. Bill Howard continued to oversee making prototypes for each of the new patterns in every subsequent year of the series, through 2006.

Figure 12. The first sales Flier and Catalog entry for the Schatt & Morgan first release in 1991. A Queen Cutlery adoption of the initial poster for the Case Classic Line.

The reintroduced Schatt & Morgan patterns would often create new construction problems that had to be overcome. These older patterns might have idiosyncrasies (and never came with an instruction manual). It often required Howard’s skill and expertise to understand the problem and then create the solution. It is likely this process continued through each year of the 20-year Keystone annual Schatt & Morgan series, anytime new patterns, blade combinations, or new handle materials were used. If knife making were easier there would have been more companies making knives of Queen’s quality.

In addition to the knives themselves, there were other production concerns. For example, steels needed to be re-evaluated for use in this type of cutlery that would both appeal to collectors and to those who bought the knives to be carried in pocket and used on a daily basis. The wooden display cases were an additional cost center. Additionally, the knife boxes for these knives themselves were relatively expensive and had to be custom made, as decisions had to be made about the size of a box and whether or not boxes were “wrapped” (the brown S & M paper-covered tops with labels and white bottom halves of the boxes). We believe Queen used six different boxes for different sized patterns.

It should also be noted that during this time period a positive quality trend also could also be found emerging in the standard production catalog knives as well, for example the Robson ShurEdge and Pocket-eze knives that they produced beginning in 1993 were also of the highest quality. The Queen Red Ice series and the Burnt Bone series were similarly offered in limited editions for only a short time, both in modern acrylic and one in desirable bone scales. Queen produced those knives in currently patterns available in their catalogs to reduce tooling costs. Over time, the Burnt Bone series has increased in value.

We will not attempt any detailed history of the knives that are now referred to as the “Schatt & Morgan Keystone Series” since those knives have been well documented in several detailed earlier references. A concise summary of the 20-year history of Schatt & Morgan Keystone knives was published by David Krauss in Knife World (2007, 2010). Also, Krauss’ book, American Pocketknives (2002) provides a much more thorough and detailed history of the Schatt & Morgan brand.

One of the more significant aspects of distributing and marketing the Keystone Schatt & Morgans was that Blue Grass Cutlery was not a primary partner. The boxed sets were sold initially by A.G. Russell through its catalogue and on its Internet site. Later, Clarence Risner became the primary distributor. Queen developed special full color fliers and catalog inserts for each year, (as noted in Figure 12, above) which were widely publicized and used by its own sales force. Blue Grass Cutlery might not have enjoyed the new competition for premium knives, though it is reported that David Scott did not object when John Wyllie described Queens plans for using older Schatt & Morgan tooling (Tim Scott, 2023). A Queen perspective suggests that Queen did send a large set of early Schatt & Morgan dies to David Scott at Blue Grass (although Queen did not send any dies used in any of Queen’s contracts with Blue Grass, or dies that would be used in Queen’s new Schatt & Morgan series). Queen and Blue Grass continued their work on the Winchester and John Primble contracts, though there may have been contractual changes in those joint projects that have not been made public.

A Fire in Queen’s Press Room, 1994

While not previously mentioned in any histories of Queen Cutlery, these dramatic increases in quality and production of collector knives took place after a significant fire destroyed the building Queen owned across Chestnut Street from the Main factory building in Titusville on the evening of November 17th, 1994. A story and photograph in the Titusville Herald covered the fire on November 18th. Five days later a second story in the Herald (11/23/1994), covered the Fire Marshall’s decision that the fire was accidental, starting in the wall behind an electric melting furnace in the southeastern corner of the building.

Figure 13. Titusville Herald, 11-18-1994 story and photo of Queen Cutlery Fire in Press Room.

The fire was a serious impediment for the company. While the walls remained standing, the roof fell-in on all the machinery and the water and smoke damage were significant. The fire completely destroyed the function of the Press Room, the only source for blanking out blades, springs, liners, and bolsters (all the basic parts of any pocket knife) including the new Schatt & Morgan line and the Rawhide and Chipped Bark catalog regular production and all the premium lines of SFOs Queen had contracted. The fire also eliminated the compressor room, steel storage, and some traditional heat treatment salt bath equipment. The damage to the building was never repaired over the 23 remaining years the of the company’s history. Major changes were immediately required. Production had to be stopped while the machinery was salvaged and repaired. Due to insurance settlements delays, the critical presses had to be moved to a warehouse in Buffalo, NY, (approximately 130 miles, one-way) owned by Servotronics for several years to regain production capacity. Queen had to transport all tooling for any particular knife pattern, the required steel, brass, and nickel silver material to and from Buffalo, to hire and train crews in the Buffalo area, and regularly send supervisors back and forth. Reportedly, Queen had to pay rent to Servotronics.

These increased costs had to be factored into all wholesale costs for all Queen knives including Schatt & Morgan, Queen Catalog knives, and special factory orders, such as continuing Blue Grass Cutlery or Case/Parker contracts. Eventually, presses were moved to the Ontario knife company facilities in Franklinville, NY, but it was not until Bill Howard became plant manager in 1997 that all press and knife-making functions returned to Titusville and made more efficient. (Bill Howard, personal communication, 2022)

Because the Schatt and Morgan annual Keystone knives were expected to be ready for market each March, the first four years of the series, Honey Bone, Red stag bone, Winterbottom bone, and Orange Corncob bone, were prepared ahead of the fire, but the highly valued stag series in 1995, the Emerald Green jigged bone in 1996, and the Deep Blue jigged bone in 1997, were affected by the transition. It is very surprising that this crisis has never been mentioned. It is a tribute to Queen’s supervision that no was no loss in the quality of knives produced, (including Case Classics and Winchester series) during this time.

Conclusion and summary

In the middle 1980’s, Servotronics’ emphasis on “top-down management” from the Franklinville office of OKC produced very little space for input or innovation from anyone in the Titusville plant. Ironically, the 1984-86 difficulties and the reduction in staff, workload, and a more relaxed local management style, allowed key employees an opportunity to learn how to find and repurpose some of the company’s antique tooling and to build strong personal/business relationships, especially with Charlie Dorton, George Smith, and David Scott. Queen, in “partnership” with those three men led to mutually beneficial projects: the production of knives known today as “John Primble”, “Winchester”, and the “Case Classics.” We believe that the resulting improvement in Queen’s bottom line finally got the attention of the corporate offices in Franklinville and Buffalo and allowed the company a little more autonomy. In 1990 Queen Cutlery was authorized to work on their own premium line of knives, like the SFOs they were already making for Blue Grass Cutlery and others.

There is no evidence that the idea of producing “collector knives” was ever a concept or strategy that emerged from Servotronics management over the 20 years covered in these four articles. It emerged from the Queen plant managers and salesmen who noticed that Queen SFO knives, Winchester, John Primble, and Case Classics, all were selling well at higher price points than Queen marked knives. We maintain that the idea of a premium Queen knife emerged from the vision of these cutlers in the factory and salesmen in the field as they noticed Charlie Dorton’s influence on a new generation of cutlers, among them Bill Howard. Howard and others in the factory were getting their hands dirty, working with old machines, and understanding well-defined criteria for “quality” in each component of a completed knife. Gradually they got much better in consistently producing finer knives “made the old-fashioned way.” There is no doubt that Charles Dorton was critical in this process.

There is no mystery here. One must first love knives and then come to work every day to with the necessary dedication. Then, to learn the skills to produce the best product one can. That, coupled with training, supervision, and oversight will ensure that the goal of high quality becomes infused in the culture of the company. Customers will notice and respond. This is the crux of Queen’s success in making collector knives – high quality over mere quantity.

The following is Bill Howard’s comment about the role of Charlie Dorton in his own career.

“Charlie Dorton was always kind and very helpful to me. He was instrumental in helping me move forward with opening Great Eastern Cutlery Company. He gets no acclaim in the traditional pocket knife industry for his accomplishments. When there became a craze in collecting and trading old pocketknives, he not only was leading the way, he had the vision and determination to reestablish an entire lost industry. Almost every popular manufactured collectable pocket knife brand since, can be directly linked to him. After meeting Charlie, and him turning me on to the history of pocket knife manufacturing and quality pocket knives, I wanted to do the whole damn/grande thing. I have been very fortunate to be in the right place at the right time and to have met and worked with the right people. He was a legendary person to me!”

(Bill Howard, personal e-mail, 10-15-2022)

NOTE: We are sorry to report that we were unable to interview Charles Dorton despite frequent searches. His business friends have not talked with him for many years, and their comments were that he was not willing to talk about his role in collectable knives. If he is still alive, its estimated that he would be about 83, but we have had no success in contacting him. We continue to hope that sometime we will be able to add his personal perspective to this history. We have also been unable speak with or to discover any information about John Wyllie. David Scott died in August 2013, at the age of 69 years, in Manchester, Ohio. During his lifetime he helped Blue Grass achieve a strong foundation and was a successful businessman in the Manchester, Ohio area (Meeker Funeral home, Obituary, 2013). We regret not being able to talk with these men and to get their perspectives on the events covered in this article. We were able to have some preliminary conversations with David Scott’s son, Tim Scott, current President of Blue Grass Cutlery, and his comments have been helpful.

Please be aware that this is a first edition article and we would appreciate any comments or suggestions for improving it. Thank you.

References.

https://www.allaboutpocketknives.com/content/knife-manufacturer-specific-research/case-classic-knife-reference-guide/

Anonymous. The History of W.R. Case & Sons and Related Companies – Part 1. Knife Talk: (knifetalkin.bogspot.com).

Anonymous. (2022). “Winchester Black box knives”, currently under “historical knife spotlight”. https://queencutleryhistory.com/

Culpepper & Co. — Fifty Fifty Productions. A brief History of Culpper Company, and the modern companies that have sprung from it.

Howard, William (2020, 2021, 2022, 2023) Personal Communication

Krauss, David (2002) American Pocketknives: The History of Schatt & Morgan and Queen Cutlery. 236 pages. Krauss Publications, 3260 Euclid Heights Blvd, Cleveland Heights, OH44118. Available online at:

http://www.americanpocketknives.com

Krauss, David, A. Ph.D, (2010). Schatt & Morgan Sets, 1991-2010. Knife World, p. 1, Vol. 36,7, July. Knife World Publications. P.O. Box 37927, Knoxville, TN, https://knifemagazine.com/knife-magazine-archives/2010s-knife-magazine-archives/2010-issues-of-knife-magazine/

Krauss, David, A. Ph.D (2007). 17 years of Schatt & Morgan Sets. Knife World, p. 1, Vol. 33,3, March5, May. Knife World Publications. P.O. Box 37927, Knoxville, TN, https://knifemagazine.com/knife-magazine-archives/2000-2009-knife-magazine-archives/2007-issues-of-knife-world/

Meeker Funeral Home, Manchester, Ohio, (2013). https://meeker funeralhomes.com/obituary/David-Scott.

Parker, Jim (1994), Pocket Knives Traders Price Guide, Volume 2. Published by James Parker Trust, P.O. Box 23852, Chattanooga, TN 37422.

Scott, Timothy (2022, 2023). Personal Communication

Shearer, Donald, (2022) Personal Communication

Smith, George (2022) Personal communication

United States Economy – A Brief History – The 1980s (countrystudies.us)

Voyles, Bruce (2020) Bulldog Brand: Origins and First Generation knives. Knife Magazine, May 2020, pp 44-47.

Witcher, Gerald, (1999). Counterfeiting Antique Cutlery. Published by National Brokerage and Sales. (out of print) ISBN 10: 09661012800.

Queen Cutlery Guide.com sites

Lago, Krauss, & Fisher (2021). Queen-Cutlery-Servotronics-early- experience-with-collector-knives-1970s.-1-28-2021.pdf (secureservercdn.net)

Dan Lago, David Krauss, Fred Fisher, 2022. Collector Knives for Queen Cutlery & Servotronics, 1980s -1984. 1 6-2022 (soon to be published)

Lago, (2021) The-National-Knife-Collectors-Association-bullhead- 1981-1-28-2021.pdf (myftpupload.com)