Dan Lago, David Krauss, Fred Fisher, 3-14-23 First Edition

Introduction

This is the third article in our series of Queen’s transition from a basic tool-making cutlery to a highly regarded maker of collector-grade cutlery. The first article covers 1972-1980, the second covers 1980-1984. This one adds the years 1985 to 1987, when Queen, working with Charles Dorton and Blue Grass Cutlery made huge strides in creating collector grade knives. We expect a fourth article will complete the transition of Queen to a major producer of collector knives in the period 1988 – 1998.

This story touches on Queen’s long-term collaborative relationship with the then recently formed Blue Grass Cutlery Company. As we understand it, the relationship between Blue Grass Cutlery and Queen Cutlery was complicated and at times contentious. As was often the case in the knife industry, projects were conducted interpersonally and casually, with little documentation available to us. In a very real sense this series of articles begins a transition from the oral history common among earlier generations of knife collectors to a more formal, written history. It is a start that may eventually be improved by stronger evidence than collected personal recollections.

During Queen’s financially difficult time in the middle 80s, we know that Blue Grass Cutlery offered to buy Queen (and Ontario Knife Company) outright, but the owner of Servotronics, Nick Tribovich (senior) would not accept the offer. Queen went on to have many successful contracts with Blue Grass despite a series of difficult issues and negotiations. When the dust had settled, numerous now-valued collector knives grew out of these projects. These successes helped save Queen from an early bankruptcy and provided a solid foundation for Blue Grass Cutlery, that still sells Winchester and John Primble marked knives.

There is obviously a very interesting history in the business dealings between these two companies, but this article focuses much more on the actual approach to producing fine traditional pocketknives using modern methods since we do not have access to adequate, verifiable information. So, this is a story of several men who learned the skills necessary to bring back the art of producing modern knives that had all the detail and appearance of pocketknives of the much earlier “golden age” of knives from the last years of the 19th century and the earliest decades of the 20th century.

Charlie Dorton and Queen Cutlery Collector Knives.

Charles Dorton’s role in Queen was first mentioned in two articles by Bruce Voyles (2020, 2023) in Knife Magazine, and Dorton’s name has not been mentioned in most historical articles to date. He, and his partners need to be acknowledged in Queen Cutlery history. Our second article in this series introduced William “Bill” Howard to Queen collectors and covers his early career at Queen Cutlery. This history owes a great deal to interviews with Bill Howard (personal communications, 2020-2023) and others, to develop a more intimate view of Dorton’s role with Howard and Queen Cutlery.

The 1970s was a critical time for knife collectors as interest in early pocket knives surged and older knives became highly valued. Some makers began to make counterfeit knives to take advantage of that interest. Please refer to Gerald Witcher’s (1999) book on the successful practice of counterfeiting old knives during this time. Frank Buster began to sell “early appearing,” beautiful pocket knives named “Fightin Rooster” knives made in the Friedrich Olbertz factory in Solingen, Germany in 1975, and his success led Charlie Dorton to use the same German cutlery to produce Bulldog Brand knives in 1978, through 1987.

Charles Dorton and friends were involved with early knife shows across the South, primarily Tennessee and Kentucky, throughout the 1970’s and with the success of “Fightin Rooster” and “Bulldog Brand,” he and fellow entrepreneurs were busily engaged in exploring how to make these kinds of knives in the United States. So, beginning in the late 1970s, he began travelling with George Smith, owner of Hardin Wholesale of Kenova, West Virginia, whose family had a long history of selling knives in the region to strengthen their understanding of the American cutlery industry.

David Scott was a friend of George Smith and involved in this pursuit. In an early move, when his father died in 1977, Scott formed a company with his first cousin, “Davis” (first name not known at this time) to work in the growing collector knife arena, named with their initials as S & D Enterprises, based in Manchester Ohio. The new company provided David Scott with a vehicle to employ his widowed mother so she could earn a living. At that time George Smith introduced Charlie Dorton to David Scott, so he would have better luck distributing his newly made Bulldog Brand knives. Working out of his home basement, Scott built a market for the Bulldog Brand and eventually sold over 90% of all the first-generation Bulldogs. S & D Enterprises also made some highly valued German knives, including a few of the Bulldog brand, but eventually shifted to making display boxes and cases and is still doing business in Manchester Ohio as S & D & T Enterprises (Tim Scott, 2023).

Eventually, George Smith and David Scott incorporated their interests to create Blue Grass Cutlery at the very end of the 1970s, (with Smith as President and Scott as Secretary/Treasurer), though the details and timeline of these corporation changes are not available to us. This does show, however, that Dorton, Scott, and Smith were working together early-on and deeply committed as businessmen to upgrading the availability of fine pocket knives.

As another part of their knife business, Charlie Dorton and George Smith would schedule trips to many northern cities, where they would sell hardware supplies from a large van. They were also on the look-out for, and would buy old pocketknives and knife-making equipment. They also visited hardware stores in search of items for re-sale, and most importantly for our story, visiting old established cutleries to examine the settings and tools where many famous old knives had been made. They would apply the knowledge they learned from their travels regarding how earlier pocket knives had been made, as well as their understanding of how those methods changed as cutleries moved west as the U.S. population expanded in that direction.

Dorton and Smith would purchase newspaper advertisements in each town where they planned to buy old cutlery and sell hardware items. They looked at and evaluated 1000s of knives and as they polished and rehabilitated these old knives, learning even more details of their construction. Finally, and perhaps just as importantly, they developed a keen understanding of which of those knives sold for more money as they returned to knife shows in their home region to sell their efforts.

With a discerning eye after handling thousands of old knives, Dorton became expert on what traditional pocketknives would meet the preferences of serious collectors. He was widely acknowledged “as a perfectionist” about the detail of how pocketknives should look and perform. And now as the owner/distributors of Bulldog knives the group had more money and connections to work with.

Because Queen was known for having been at the same location since 1902 and still had early Schatt & Morgan equipment, Dorton and Smith often included Titusville and the Queen factory in their travels, and would discuss knives and resources there with Bill Howard. Charlie Dorton and Bill Howard hit it off and developed a close, mutually valuable working relationship. Don Shearer, (Personal Communication, 2022) who was Queen’s Plant manager at that time, hoped good things would come from Dorton’s and Smith’s regular visits. He very much enjoyed working with George Smith. Shearer recalls, Dorton and Smith would prowl through the factory buying old tooling and making large buys of old dies, parts, and inventory from the basement vault where “seconds” were stored. Once assembled and marked, those knives were sold to Smoky Mountain Knife Works (SMKW) by Smith and Scott.

Dorton’s earliest project with Queen was having Bill Howard construct new dies for making parts for an Aerial lever lock knife reproduction that was popular with collectors, but hard to find. Howard made the dies – his first ever. Although Dorton had the knife built elsewhere, this was an important first step in making dies that were consistent with earlier knife making technologies. Their collaboration was quite successful. Queen made 3 or 4 editions of 200-300 parts each for complete knives for Charlie Dorton. Dorton paid in cash which again was a great help to Queen in those tight times. Those reproduction Aerial lever lock knives can still be found in collector circles.

Another notable project of the time included a five-knife set of Queen’s small serpentine pattern (#34). These knives with 2 blades etched with shotgun gauges, included bone scales, federal style shields, and were tang stamped “Winchester.” They were provided to buyers in a box. There are different perspectives on how the set was boxed (or different methods used in boxing the sets). Some say in a cardboard “Winchester Black box with a fold up lid and cut-outs for the five knives.” Others claim “the boxes were wood, likely produced by David Scott’s company S-D Enterprises (George Smith and Bill Howard, Personal Communications, 2022). Recollections of the edition size also differ from 1,000 to 4,000 sets, a very large contract at that time. (Unfortunately, we have been unable to find any photos of that knife set.) Don Shearer recalls that Smith and Blue Grass paid promptly, and those big purchases helped to keep Queen in business in the mid-1980s.

Charlie Dorton’s collaborations with Bill Howard grew through the middle 1980s. He would visit with Howard as often as once a month and travel through the factory making suggestions on how to improve the set-up of different machines. Bill Howard has noted, “He was a perfectionist and showed me many things I had not known about making a fine knife!” He particularly remembers sitting in Charlie Dorton’s car outside the Titusville Cutlery and carefully examining a set of Bulldog Brand knives that Charlie was very pleased with. “At each step in the process of making a knife, he helped us to see what would define quality. I listened and worked hard to put his ideas into practice!”

On one of these trips Dorton suggested he was getting tired of traveling to Germany, the increasing costs of producing the knives there, and the language issues. He wanted to consider working with Queen and making knives in America. He was preparing to cut his ties with Olbertz in Solingen, Germany and relinquishing his ownership of the highly successful Bulldog brand, which he did in 1987. This ended the “first generation” of that brand.

Another business opportunity soon emerged when Belknap Hardware was auctioned off in 1986. George Smith and David Scott purchased the remaining stock of John Primble knives, and the John Primble trademark for $50,000 for Blue Grass Cutlery (George Smith, personal communication, 2022). The John Primble trademark went back into the 1840s – it had a very strong history (Tim Scott, 2023).

Smith, Scott, and Dorton, then visited Utica Cutlery in Utica, NY, which was making the John Primble knives at that time and still using some of the original tooling. Utica Cutlery Co. was established in 1910 by former Camillus employees Samuel, Abraham, and Joseph Mailmen along with other investors. They developed a very elaborate knife making process. They were clearly set up to make big, efficient production runs and their knife designers/engineers were outstanding. Utica Cutlery made many brands with their own and others’ trademarks, (including Caterpillar, Browning, Klein, Proto Tools, Mountain Quest, Pocket Pard, Featherweight, Seneca, Agate Wood, American Maid, Iroquois, and their most famous “Kutmaster”). They also serviced huge numbers of jobbers who sold knives across the country (iknifecollector.com; Knife talking, websites).

To examine Utica’s old tooling is the first step to understanding their process of traditional knife making. It is like traveling back in time to pre-WWII cutlery techniques. By the middle 1980s, other American cutleries were streamlining their knife offerings to a very limited set of patterns with different handles materials to maximize efficiency. It is our understanding that Queen, for example, offered approximately 33 pocketknife patterns in three handle materials – Chipped Bark (Delrin), Rawhide (wood), and Pearl (in very few patterns). In comparison, the Utica Cutlery Pattern Guide, which they used to sell to customers who wanted to buy special factory orders, listed 1,125 patterns, (which was thirty-four times the number of patterns that Queen could readily produce in the 1980s). Blue Grass Cutlery still has the original of this Guide, and Bill Howard still uses a photocopy of that large book, provided to him by Charlie Dorton, as a critical resource.

At the time of their initial visit, Dave Allen, (Senior) President of Utica offered Blue Grass Cutlery a huge amount of tooling and parts, (and a very beautiful display of pearl-handled knives) at bargain prices as Utica planned to leave the traditional pocket knife market at that time and move further into tableware and restaurant equipment. George Smith and Dave Scott paid immediately for all of it and started to haul the large lot of tooling and supplies (several trailer truckloads) back to Manchester, Ohio. (At the present time Utica Cutlery still does have some pocket and fixed blade knives in their product line. Utica USA – Knives and Cutlery Made in the USA Since 1910 )

To get a sense of their special factory order business, George Smith reports that Blue Grass obtained between 400 and 500 different dies for making individual tang stamps in their purchase of Utica tooling (George Smith, 2022). It also dramatically increased George Smith, David Scott, and Charlie Dorton’s interest in Queen because neither the original owners, nor Servotronics had moved to modernize their equipment. And that equipment could be made to work with the earlier style of Utica’s tooling.

Figure 1. Utica Cutlery, Utica, New York was the source of many valuable purchases of old tooling and knife making supplies by Blue Grass Cutlery. It offered a new opportunity for Queen Cutlery’s old machinery to have new life.

Why the Sudden Interest in Bone Handles?

Pete Cohan (R.I.P.! Obituary, Knife Magazine p. 29, September, 2021) was a former President of the National Knife Collectors Association, and oversaw the development of the NKCA Museum. He was widely respected for his comprehensive knowledge of the cutlery industry. He once shared a story with one of our authors (F.F.) about the sudden emergence of Delrin handles on American knives, as follows: “Schrade Cutlery was a major competitor in American pocket knives. In 1958, they had a fire in their bone jigging facility. Instead of repairing and rebuilding, they made molds of several bone handles and immediately switched to Delrin plastic. This material was more durable and dimensionally stable unlike some earlier plastics like celluloid or bakelite. It did not require the multiple steps to prepare bone handles for use, so it was much cheaper to use and had very practical advantages for tools. Most importantly for the bottom line, Schrade reduced the costs of its knives by around 30%! Case, Camillus, Queen, and other cutleries had to respond and shift to the new material quickly to stay competitive. Robeson was committed to large stocks of Strawberry bone and did not invest in the new technology. It was out of business by 1963” (As retold by Fred Fisher).

This story is strongly supported by “Old Codger-64” (an expert with over 60,000 posts in the Schrade group on Blade Forums) in a discussion of Schrade’s rapid shift away from bone, except for certain “special knives and commemoratives.” He also claims Case and others continued to use bone sparingly but no longer in any catalog knives (“Old Codger-64”, Schrade Scales, Blade forums, 2009).

Queen quickly adapted to this change, starting to use Delrin handles in 1959, beginning with “Burnt Orange” Winterbottom, and later with black or brown dyes over light colored Winterbottom Delrin which they used exclusively for catalog knives until about 1980. They also used some red, amber yellow, and black Delrin in the 1970s. Please refer to David Krauss’ American Pocketknives, 2002, pp. 115-122, for an informed discussion of Rogers bone and its follow-up company, Crown Plastics, with owner Steven Moskel, who provided Queen with plastic versions of Winterbottom “bone,” in synthetic Delrin its use by Queen Cutlery.

In a very few instances, Queen did use bone handles in commemorative knives; reddish sawcut bone on the 1972 Drake Well commemorative Barlow, and Rogers bone in the Master Cutlery Collection in the late 1970s to 1981. All these knives were made with bone scales already in inventory, none were bought or produced in-house (Fred Sampson, personal communication, 2022). So, just as knife users liked the lower prices and durability of plastic handles throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, by the 1980’s collectors wanted special knives that used traditional handles hafted in old fashioned ways.

From our perspective it is important to remember Charlie Dorton’s creative influence on the first-generation Bulldog brand knives that Bill Howard studied. Below is a link to a good resource on the “Allabout pocketknives” website which shows color photos of documented first-generation Bulldog brand knives, including several gunstocks with dark brown bone scales. 1st Generation Bulldog Brand Knives (allaboutpocketknives.com)

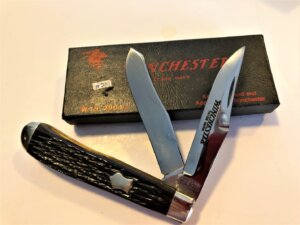

Figure 2. A First-Generation Bulldog brand gunstock in brown bone as an example of Charlie Dorton’s influence on the John Primble and Winchester knives promoting very traditional bone scales. (This photo is copied and enlarged and does not do a very good job showing the quality of the knife – please use the link above to study other Bulldog first-generation knives: 1st Generation Bulldog Brand Knives (allaboutpocketknives.com).

So, moving back to the Utica sale, imagine Dorton and his friends digging around a darkened New York Mills warehouse owned by Utica Cutlery when they discovered old bone that revealed the earlier techniques that had been used in making those bone handles! They found many bags of old bone prepared for handles for pocketknives buried under water in the penstock that ran throughout the first floor of the old warehouse. Penstocks were used in early days to provide waterpower to operate knife-making machines. The men had no idea how old the bone was, but clearly it had been forgotten for many years. These bits of bone had been cut to shape for knife patterns and were contoured, jigged, and dyed to fit a frame very precisely. The bone they found was an exact fit for a scout knife pattern. Now they had a good supply of old finished bone that led them to want to produce new bone. However, since Delrin and various acrylic handles had been adopted throughout American pocketknife companies in the later 1950s and early 1960s, the techniques and necessary skills for working with bone handle materials had been lost in the intervening 25 or more years. So, the projects that Queen and Blue Brass Cutlery were planning required a great deal of experimentation – trial, error, and improvement.

On one of their other buying trips a bone cutting machine that had been out of service since 1961, was purchased from Crown Plastics (formerly the Rogers bone company) in Meridian/Rockfall, Connecticut. George Smith and Charlie Dorton brought the machine to the Queen factory themselves on a flatbed truck. Charlie Dorton gave Bill Howard the initial insight into how to use the machine. Howard, along with his maintenance man, and Queen machinist Blaine Donahue, who had an extensive mechanical background, cleaned it up and got it running. They fabricated special cutting tools for the Rogers machine and did test runs.

That machine was ultimately transported to Blue Grass Cutlery in Manchester Ohio, and Bill Howard went there to demonstrate how to use the machine to jig bone knife handles. He recalls that David Scott was very interested and friendly during that work. The machine was set up in the building that housed S & D Enterprises. Blue Grass acquired the bone slabs, which they jigged, and then sent them to Charlie Dorton to be dyed. A number of Case Classics knives and the special factory orders by Moore Maker for a series with jigged yellow bone were the first use the old Roger’s bone machine. Tim Scott still uses the jigging machine for contemporary John Primble knives, and it works exactly as it did 30 years ago. (Per Howard, 2023).

Around the same time, Bill Howard devised a process adapting a contemporary milling machine to jig the bone in the Queen 1988 Muskrat (see Figure 1 in the fourth article). Gradually suppliers of handle materials for knives started to increase their offerings of bone to the industry. Even in 2022, there are significant variables related to the quality and sources of bone available to knife makers. Bill Howard reports currently, that those early experiments brought adequate results, but in the intervening years he has learned that the selection of bone, the techniques for cleaning it, the approaches to machine-jigging, and dying it, has required much study and effort to achieve his current level of quality. These methods make some modern bone much more durable, and more beautiful. Don Shearer thought that learning to use the bone jigging machine recovered from early cutlery manufacturing was one of the most valuable assets in making collectable modern knives (Shearer, 2022). And so it was, that the rediscovery of old methods was accomplished one step at a time for each part of the new, traditionally made knives.

Making the John Primble and Winchester Knives.

Back in the day, Charlie Dorton was often accompanied by Smith and Scott on his trips to Titusville, with Dorton, as the “knife designer,” (George Smith, personal communication, 2022). Dorton was instrumental in getting the old Utica dies and parts, owned by Blue Grass Cutlery, to Queen in Titusville to make knives for Blue Grass. Queen was the logical place to build them as the cutlery had the old machines that would work with the dies. Queen also had a good deal of capability to expand their output, and Dorton felt confident that Bill Howard had the skills necessary do the job. However, Dorton provided the internal review to make sure the knives met his high standards.

“Blue Grass Cutlery now owned thousands of various tools used decades before for building all the old Utica knives and subcontracts. Charlie Dorton spent much time in Manchester studying through all that old tooling and sorting them into their appropriate patterns and then bringing those tooling sets to Queen. He selected old traditional patterns that were not being produced in the present day by any of the contemporary cutlery companies. He had a vision of what tooling would work together to make the completed knife he envisioned; it was a kind of genius. In addition, he made sure that each small envelope that that went with a given pattern, including a variety of “swedges” or “hobs” that could be used to allow variations in finishing of bolsters (and blades), that would allow for fine differences in how the completed knives could be made to look. I would then have the tooling cleaned, altered if necessary, and sharpened. Then they were used to make sample parts to be assembled into sample knives. Originally when blanking the samples, we would make additional parts and finish them. They were branded with an obscure old name and sent them down to Charlie Dorton who would buy them. That would offset the cost of making the sample run. After making the samples I would determine which tooling needed to be remade to produce an actual production run.”

Bill Howard, 2022

Those old tools with some modifications would work at Queen because Queen, although still in business, was uniquely stuck in a 1940’s, 50’s, 60’s style/era of manufacturing. The Queen Titusville plant, for example, had old tooling to “coin” the bolsters rather than “stamp and sand” process used for most modern bolsters. Some of the oldest Schatt & Morgan blade dies were designed to be manually hammer forged after pressing and then manually hand-filed to the correct shape. Those dies could not be used. Others simply blanked out the blade shape and needed much less trimming. After trial and error, some dies were modified or discarded, and new ones made. So, each of the old dies for John Primble, Winchester, knives had to be adapted to work effectively with the available presses. That was a task accomplished one part at a time for each knife pattern.

Dorton continued his visits and worked closely with Bill Howard to complete these knives in the Titusville factory. He reviewed small trial editions until they met his rigorous quality evaluation. Since the bone for “scout” pattern had to be sanded to fit other patterns, leaving a lighter edge which was unacceptable to Dorton’s focus on details, so refinishing the old bone found in Utica warehouse once sanded, using very dark brown Feibings leather dye to get the correct appearance of old bone handles. He really liked the result and so did many collectors. The Utica bone was used for the early John Primbles and the smaller Winchester knives. Dorton and Blue Grass also found and bought old bone handle material for large size pocket knives from Boker in Germany, and others as well.

The John Primble brand continues to be made by Blue Grass Cutlery, manufacturing the knives themselves. Now this old brand name has been produced by Blue Grass for over 35 years, demonstrating a successful strategy of making reproductions of old brands, and still very attractive for collectors.

Figure 3. A John Primble brand Stockman knife from 1987, made by Queen as an SFO, and delivered to Blue Grass Cutlery. Note the marketing with the tang and box showing an old “India Steel Works” rather than the more recent “Belknap Hardware, Louisville, Kentucky” tang, indicating the commitment to older looking but modern knives. (Image by Sanders Knives, Allabout Pocketknives.com, used with permission).

Winchester Knives.

While at dinner one night, likely in 1986, Dorton, Smith and Scott decided “Why not expand, our offerings with a well-recognized old American name”? They decided that “Winchester” would be a great because of its historic background in opening the American West. Some years earlier George Smith had made some Winchester-labeled knives without permission. That brought him a “Cease and Desist” letter from Winchester. However, the next morning after their dinner conversation, George Smith called the Olin company, owner of the trademark, and drove to Alton, Illinois for a meeting. There he said “I want to put you boys back in the knife business, with 5% on each and every knife, and here is $5,000 bucks to start the process,” It took 30 minutes and we had a deal.” (George Smith Personal Communication, 2022). So, with a much easier success than they had imagined, they were immediately given the right for Blue Grass Cutlery to produce a line of Winchester pocketknives. This task was then immediately transferred to Queen Cutlery, where Bill Howard was tasked to work with Charlie Dorton to design and produce the new Winchester knives.

Figure 4. Winchester Trapper (#2904 ½) at 4 1/8″ closed length in black “old Roger’s bone”, with heraldic shield. This knife was produced in an edition of 3,387. It has the well-known Winchester black box. It is easy to imagine Dorton and Howard reaching agreement on the coloring and treatment of this old bone (see p. 12). (© Fred Fisher). This knife was made on a Queen pattern, with special grinds on the swedges on both blades that closely resembled knives made in the early 20th century, such as Challenge Cutlery trappers.

Figure 5. A small 4-blade Congress (#4935) in Pearl with a “bar” shield. This knife is 3 3/8″ closed length and was offered in an edition of 360. Two other versions were offered an “old Rogers black bone” in an edition of 1,380, and stag handles in an edition of 486. (© Fred Fisher). This knife was made almost exclusively on Utica tooling and the pearl scales were provided by Masecraft, one of the few handle material providers at that time, (per Bill Howard, 2022).

The introduction (for Winchester reproductions) of Jim Parker’s “Pocket Knife Traders Price Guide, Volume 2, pp. 294-297, (1994), differs from the history we have established from current interviews. Parker says that Blue Grass Cutlery had “old Winchester dies and tools from before WWII and truckloads of old bone”, and credits Blue Grass for that information. It currently seems to us, based on the corroborated recollections of Scott, Howard, Smith, and Shearer, that Blue Grass Cutlery acquisitions from Utica Cutlery are more likely to have been the source of the tooling and bone. It is likely that it is a combination of dies, approximately 50% from Utica, (now owned by Blue Grass Cutlery), and 50% Queen dies were used. Blue Grass supplied the bone from their contacts with purchases from many different old-time cutleries. (Bill Howard. Personal communication, 2022).

Figure 6. As the age of classic pocketknives “reproductions” became more important, reputable makers added features which would help collectors differentiate the modern knives from the originals. The Blue Grass Winchester knives made by Queen all featured the model number assigned by Blue Grass and the year of production. This is the pile side of the same knife shown in Figure 4, the trapper in “Old Rogers Bone”. (© Fred Fisher).

Each of these model numbers and year of production tang stamps cost approximately $175, (subcontracted to Henry Evers Company), depending on the detail of the tooling to make the stamp. Queen included that cost in the wholesale price for each knife, which Blue Grass amortized across each edition of knives (Bill Howard, 2023).

Jim Parker’s Guide agrees (pages 294-297) that the Winchester reproductions have year of production and pattern on the pile side, just as our figure 6 shows. Blue Grass Cutlery used the historical Winchester logo on a black box which has since become highly sought after among collectors. Each box also has the model number printed prominently on the top of the box. This contract was a huge benefit to Queen in the late 1980s and through the middle part of the 1990s – we are not sure when specific contracts were changed or renegotiated, though some Winchester knives were still made by Queen as late as 2006. Parker’s Guide indicated that Queen delivered from 1987 through 1994, over 90 different patterns and handle treatments to Blue Grass Cutlery, producing by 1994, in excess of 121,000 knives! That is much larger than the Parker-produced Case Classic line.

There is also an interesting article in Queencutleryhistory.com as “Winchester Black Box knives” that discusses these knives. (Queen Cutlery History.com)

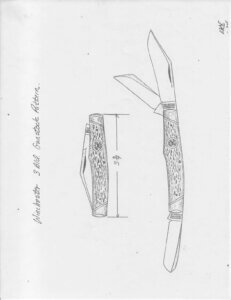

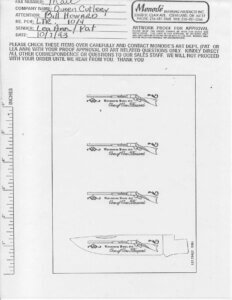

The next two Figures, 7 and 8, are from the Queen factory internal “Design Book” used by Queen for completing these SFO knives. It was found in the attic of the Queen factory in Titusville during the bankruptcy auction. The drawings were used as ongoing “sales pitches” to maintain good communication between a client and internal staff regarding completion of a specific knife. Many images are hand-drawn by Bill Howard (such as figure 7). Figure 8, shows details from a shipment of blade etchings for knives sent to Bill Howard to be completed in the Titusville cutlery for the Winchester series knives in 1993. These drawings add significant support to our evidence that Queen made the Winchesters at least through 1993. Some Winchesters may have been made by other sub-contractors after 1993.

Figure 7. Bill Howard’s pencil drawing of a Winchester 3-blade gunstock in the Queen Design book, 8.5″ x 11″. Note initials WLH in upper right corner. (© Dan Lago).

Figure 8. An “Art Proof” from Monode Marking Products for confirmation of the blade etch for a special edition of 1-1000 for the Winchester Model 1873 knives returned to Bill Howard, 10-7-1993. Since this bronze handled knife is shown in collections, and this “proof” had to be approved by Bill Howard before the knife was completed, it is strong evidence that Queen was the producer. (© Dan Lago).

While it has often been a point of confusion among knife collectors, it now seems very clear to us that David Krauss’ history (2002, p. 161) was correct in stating that Queen Cutlery, not Blue Grass Cutlery’ factory in Manchester Ohio, was where the early Winchester and John Primble knives were made. It seems these knives were special factory orders (SFOs) from Blue Grass Cutlery, using some tooling and bone owned by Blue Grass, and with Charlie Dorton working with Bill Howard on design and quality control. Given the nature of the pocketknife industry and the lack of written documentation, there have been claims, without evidence, over the years that Blue Grass Cutlery made the knives, or that Queen made the parts but they were assembled somewhere else. We think the fact that the machinery to use the various dies was at the Queen factory, that some of the knives used Queen dies, and the quality of the knives, strongly suggest that Queen actually made them. And that work led directly to the company’s enhanced reputation at the end of that decade.

It is obvious that the success of these American made collector knives also provided a reputation for Blue Grass Cutlery that continues to the present time. It seems to us that both companies hoped their version of the collaboration would remain the dominant story. It is unfortunate that neither version of the histories have given sufficient credit to Charles Dorton for his critical work that no doubt paved the way for their respective successes. Charles Dorton was “All about the knives – a true perfectionist.” (Bill Howard, 2022.)

We will return to the fourth, and final article on Queen’s transformation into a “collector” cutlery with an upcoming article on the same players working together to create the Case Classic series and finally the Schatt & Morgan reintroduction in the period 1988 through 1998.

NOTE: We are sorry to report that we were unable to interview Charles Dorton for this article despite persistent searches. His business friends have not talked with him for many years, and their comments were that for whatever reason, he was not willing to talk about his role in the collectable knives’ renaissance. If he is still alive, its estimated that he would be about 83. We continue to hope that sometime we may be able to add his personal perspective to this history. David Scott died at 69 in Manchester, Ohio on August 20, 2013. During his lifetime he was a successful businessman in several industries and helped Blue Grass Cutlery achieve its strong foundation. We would have loved to have talked with these men and to get their perspectives on the events covered in this article. We were able to have some preliminary conversations with David Scott’s son, Tim Scott, current President of Blue Grass Cutlery, and they have been helpful.

Please be aware that this is a first edition article and we would appreciate any comments or suggestions for improving it. Thank you.

References.

1st Generation Bulldog Brand Knives (allaboutpocketknives.com). Photos of well documented early Bulldog brand knives.

Anonymous. (2022). “Winchester Black box knives”, currently under “historical knife spotlight”. Https://queencutleryhistory.com.

Anonymous (2021). Peter Cohan Passes. Knife Magazine p. 29, September, 2021.

Codger-64. (2009). Schrade Scales. BladeForums.com. Codger_64, (moderator) Aug 18, 2009.

Howard, William (Bill). (2020, 2021, 2022, 2023) Personal Communication.

iknife Collector. Utica,Kutmaster – iKnife Collector

Knifetalkin. Utica Cutlery Company (knifetalkin.blogspot.com)

Krauss, David (2002) American Pocketknives: The History of Schatt & Morgan and Queen Cutlery. 236 pages. Krauss Publications, 3260 Euclid Heights Blvd, Cleveland Heights, OH44118. Available online at:

http://www.americanpocketknives.com

Meeker Funeral Home, Manchester, Ohio, (2013). https://meeker funeralhomes.com/obituary/David-Scott.

Parker, Jim (1994), Pocket Knives Traders Price Guide, Volume 2. Published by James Parker Trust, P.O. Box 23852, Chattanooga, TN 37422.

Sampson, Fred (2022) Queen Master Cutler, Personal Communication.

Scott, Timothy (2022-2023). President of Blue Grass Cutlery, Personal Communication.

Shearer, Donald, (2022) Former Plant Manager Queen Cutlery, Personal Communication.

Smith, George (2022) Former initial President of Blue Grass Cutlery, Personal communication.

Utica Cutlery Website, (2023). Utica USA – Knives and Cutlery Made in the USA Since 1910. See “about” tab for a brief history. See “Products” tab for knives.

Voyles, Bruce (2020) Bulldog Brand: Origins and First-Generation knives. Knife Magazine, May 2020, pp 44-47.

Voyles, J. Bruce (2023). Vintage Queen Knives – Potential Sleepers. Knife Magazine, June, 2023, pp 46 -47.

Witcher, Gerald, (1999). Counterfeiting Antique Cutlery. Published by National Brokerage and Sales. (out of print) ISBN 10: 09661012800.

Queen Cutlery Guide.com sites

Lago, Krauss, & Fisher (2021). Queen-Cutlery-Servotronics-early- experience-with-collector-knives-1970s.-1-28-2021.pdf (secureservercdn.net)

Dan Lago, David Krauss, Fred Fisher, (2022). Collector Knives for Queen Cutlery & Servotronics, 1980s -1984. 1 6-2022. (soon to be published).

Lago, (2021) The-National-Knife-Collectors-Association-bullhead- 1981-1-28-2021.pdf (myftpupload.com)