Queen Cutlery Boxes through 2012-2017 – Daniels Family Ownership of Queen Cutlery Company

Brian Guth, David Krauss, Ashley and Joe Mick, Dan Lago, and Fred Fisher

This article seeks to give the reader some factual information about the variety of boxes for knives used during the Daniels Family Cutlery era. We will leave it to others to piece together a solid history of why Servotronics decided to sell Queen Cutlery after roughly 43 years, or why Ken and Ryan Daniels sold their share of Great Eastern Cutlery and purchased Queen in 2012, or how the company failed before 2018. As an article written in 2020, we still do not know the answers to these and many other questions about the company. That must remain for another time. This article does share some opinions about knives produced and box choices from 2012-2017.

It is clear that the Daniels Family Cutlery (DFC) made many changes in their short period of control. They introduced a number of new lines. The company also made many more custom shop and limited edition knives, and introduced a way to sell “seconds” as EDC (every day carry) knives. While many have noted the company faced issues of quality control, we would like to say they also produced many fine and beautiful knives during this period.

But this article focuses only on the boxes they used in those final years to provide collectors with a path to distinguish the DFC knives made in the Titusville factory from those knives made with parts that have come to market after the bankruptcy. Proper boxes used to hold a knife (and blade etches) are more difficult for entrepreneurs to counterfeit, while blades with Queen tang stamps could have been acquired relatively easily.

Figure 1. A few swing guard knives (#1L) boxes by Daniels Family Cutlery

Figure 1, shows the variety of boxes used by the company from 2013-2017 for a few of the many swing guards they produced. The large black box on the left was for an edition of 100 #1L in Winterbottom bone with a “bomb” shield. This type of deeper (higher) box was used by DFC for many large folding knives. The four red boxes, in two different colors show the darker red (bottom) for the two prototypes (1 of 3 for each knife) were made in 2013 and hand-lettered. The two brighter red boxes (top) were used in 2016, and show a variety of labeling; the “red jig” (topmost) was 1 of 4, all hand-labeled. The pre-printed Elk antler was 1 of 30, with additional hand-labeled details, “spear”. (Note, that this handwritten label, applied at the factory, suggests that there was probably another version of the same knife with a “Clip” blade – an example of DFC production of very small limited-edition knives.) These boxes were of similar color to the boxes used in the Robeson line and likely found in storage. The two traditional brown, Schatt & Morgan boxes on the far right were also produced in 2016-2017. Though both knives had signature bolsters only one shows “SG”(for “signature bolsters.”) it on the box label.

Purchasing knife boxes was relatively expensive. It may be that DFC repurposed existing boxes whenever they could, or perhaps purchased more, less expensive boxes to reduce immediate costs. For whatever reason, a change from traditional box formats started to emerge. Perhaps, an early sign of financial woes that grew worse in the last years?

Figure 2. Queen-labeled knives were sold with the blue label (left) that emphasized the Daniels Family “Q DFC” logo that was also used on tang stamps. Again, both red and black boxes, with a smaller adhesive label, with rounded edges were also used for Schatt & Morgan knives. Pre-printed labels were predominantly used, but some handwritten labels also occurred from time to time, especially in short runs.

Figure 3. Black boxes, not showing “DFC” but, using early 2000s “Queen steel” label were also common. At left is shown a textured box “Queen Steel” stainless label for a #85 trout knife in ACSB, and on the right. a “John Henry” stag knife (not cataloged) in a smooth black box, with traditional Schatt & Morgan label.

Figure 4. One-piece boxes used by Daniels Family in last few years. Pair of #10 Roosters (Cock fighting knives) in both Queen DFC label (right) and Schatt & Morgan label (left). Both with Pre-printed end labels. Except for the labels, these inexpensive boxes for the two different “brands” are essentially the same.

The one-piece boxes in thinner, white cardboard were a strong reflection of company financial troubles. They returned to the less costly box style from the early 1980s. These white boxes are the first time Schatt & Morgan knives were not sold in a two-piece traditional box.

Indeed in 2014, skeleton knives in various patterns sold through Bluegrass Cutlery, with both Queen and Yellowhorse tang stamps on the blades, were provided to Micheal Prater and Painted Pony Knives for customized handles. These knives were finished with exotic acrylics with enbedded minerals and with glue-on shields in very small editions. These knives were subsequently sold with no box, only with a thin, clear vinyl sleeve.

Figure 5. Swing guards with both “Queen” and “Yellowhorse” tang stamps customized by Painted Pony knives (top 3) with minerals in acrylic handles,, and the bottom knife customized by Yellowhorse knives, were sold in very small editions, but with only a thin vinyl sleeve – no box.

As our earlier article on “boxes” in the post-WWII era showed, (Fisher, Guth, Mick and Mick, and Lago, 2020) in “the old days”(1940s-1970s) many Queen knives were sold as “tools” without any packaging and most collectors have for years bought Queen knives with no sense that a box mattered. But, this was the first time that collectors of modern knives faced such minimal packaging. In fact, some Queen or Schatt & Morgans were sold to secondary sellers in the last year of the company without any box at all.

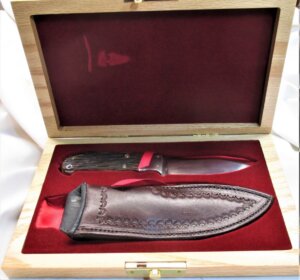

Figure 6. Joe Kious hunter in custom white Oak box, with Amber carved stag bone, 2014-15.

The Joe Kious Hunter shown in Figure 6, featured a well-crafted box by the same contractor who made boxes for the Smithsoninan Museum (Jenny Moore, personal communication, 2015), with velvet interior and bottom, inletted spaces for both knife and shealth, with ribbons to remove both knife and sheath – a very fine display box in our opinion. A much smaller edition was also done in stag (such fine boxes were not provided for Joe Kious’ coyote brown or pink micarta handled cataloged knives.)

Figure 7. A final version of a “Drake Well Commemorative” Wildcat Driller knife produced in 2014 or 2015, using the same special blade etch from 1984, and display box from the 1988, 66th anniversary efforts. This display knife provides a sense of scouring through materials left over inside the Titusville factory to turn inventory to cash. (We note that the term “Wildcat” originated in the early 1859 Titusville oil boom, from an independent derrick with a stuffed wildcat mounted on top which did strike oil. So, the choice of knife is very appropriate for the last of the Drake well commemorative knives.)

After 2015, the more expensive handle materials such as pearl and abalone started to disappear. This was likely due to the company’s financial situation and is also reflected in fewer funds spent on boxes rather than keeping traditional delivery appearances alive.

However, during the DFC era the printing on many Queen knife boxes gives collectors an opportunity to distinguish factory-made and sold knives from “parts knives” that were sold to other finishers in the company’s final years. The DFC labeled box is unique to this period, (as is their dual tang stamp with pile side showing steel used in various knives). The red and black boxes are also unique to this period. Certainly, the one-piece white boxes, often with a pre-printed label, and sometimes handwritten labels, showing small edition sizes are also associated with the company’s last two years.

Unfortunately for collectors, some of the last knives sold, including a number of Schatt & Morgan, were not boxed but sold in volume to dealers. While assembling the right colors of boxes and producing the right labels is a challenge for counterfeiters (or “part knives” sellers), the white boxes can be printed on any good software and printer as a way to add provenance to a knife if a bankruptcy blade with an earlier tang stamp is used. While the same can be said for etching, they require more expense and machinery to be practical – absence of an etch should be an alert for a collector, or an early tang stamp with a much more modern handle.

Examining a knife from Queen’s DFC production era should include study of any box that goes with it. In a sense, preparing fake boxes and new knives will not make sense unless it can be done in fairly large numbers, so it would be wise to check for the sudden availability of a knife which would likely not be easy to find in collector sources. Clearly, knowledge of Queen knives and their boxes will be very helpful to build and verify a valid collection. We hope that this article has been helpful in that regard.

References

Fisher, Fred, Brian Guth, Ashley Mick and Joe Mick, and Dan Lago, (2020). https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.109/gbh.929.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Queen-Boxes1947-to-collector-era.-4-30-2020.pdf

Moore, Jennie, (2015) Personal communication about Joe Kious boxes.

![figure 4[82] #10 Rooster Cock Fighting Knife Boxes](https://queencutleryguide.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/figure-482-q079zacbxmjiiob8fpespuh285ra2lbdrjb2zps77s.jpg)